T he French presidential election in May, won by Emmanuel Macron at the head of a freshly-minted political party, La République en Marche (REM), was followed up in June with elections to the Assemblée Nationale, the French parliament, in which REM won a clear majority of the seats:

he French presidential election in May, won by Emmanuel Macron at the head of a freshly-minted political party, La République en Marche (REM), was followed up in June with elections to the Assemblée Nationale, the French parliament, in which REM won a clear majority of the seats:

“…the President’s party … won 43 per cent of the vote, gaining 301 out of 577 seats in the National Assembly. Adding in the tally of En Marche!’s ally MoDem, and Mr Macron can command an impressive 350 seats.” (Claire Sergent, ‘French parliamentary elections: Emmanuel Macron’s party En Marche! wins majority in National Assembly’, The Independent, 18 June 2017).

Nevertheless, “At the En Marche! party’s headquarters in the 15th arrondissement of Paris, the mood [was] not the same joyful celebration that greeted Mr Macron’s own presidential election victory six weeks ago” (ibid.). The reason for the subdued response to the victory was that the turnout in the election had hit a record low. Only 43% of the electorate cast their vote for any of the parties standing. The rate of abstention or spoilt/blank ballots was an incredible 57%. And it was not a question of bad weather discouraging people from turning out: it was abundantly clear that “The four-million strong blank/null vote in that second round had itself shown a large section of voters not simply abstaining, but actively displaying their discontent with both Macron and his right-wing rival” (David Broden, ‘An uninspired victory’, Jacobin, 23 June 2017). As Al-Ahram commented: “While the REM had scored an impressive victory, Le Monde said, the party was ‘very far from representing large sections of the population… These parliamentary elections risk increasing another huge problem of our political system — its lack of representation.’

“Many seats had been gained with very few votes as a result of massive abstention, and there was a danger that the new MPs would end up simply talking among themselves given that they came from the same social backgrounds, driving real contestation of government policy onto the streets” (David Tresilian, ‘Macron win in French elections’, 23 June 2017).

Nevertheless, by comparison with REM, the number of seats gained by the various other parties which put up candidates was slim indeed: “The Conservative Republicains came a distant second with 22 per cent of the vote and 113 seats, while the head of the Socialistes quit after his party suffered a horrendous defeat. The party won just 6 per cent of the vote and 29 seats [down from the 331 seats it won in 2012]” (Claire Sergent, op.cit.). Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s France Insoumise party won 17 seats, the French Communist Party won 10 and Marine Le Pen’s Front Nationale obtained 8 seats.

Given that Macron’s political platform was most reactionary – anti-Russia, anti-immigrant, for the abolition of labour protection laws, for the reduction of corporate taxes and pro European Union, all policies firmly opposed by a large proportion of the French population, his Party’s overwhelming parliamentary success is at first sight hard to understand – and yet it was correctly predicted as soon as the presidential election was over by all the media political pundits. The only thing they got wrong is that REM did not win by as massive a landslide as they had foreseen.

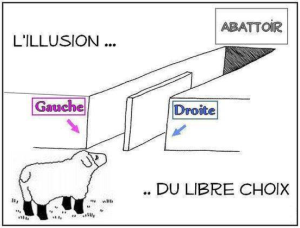

The best explanation of how Macron effected this coup – apart from the massive and overwhelming support he received from the bourgeois media – was given by the popular Paris daily Le Parisien, commenting on the results on the day following the election: “by voting for the extremes in the first round of the presidential elections [when both the mainstream right and the mainstream left candidates were eliminated] and now by their massive abstention in the second round of the parliamentary elections, French voters have expressed first their anger, and now their indifference, towards a political system that interests them less and less.”

This indifference is unlikely to last, however, as Macron begins to roll out the edicts dictated to him by the French establishment. The attempts by the previous government led by François Hollande’s Socialist Party to reform French Labour Law by considerably undermining worker protections – strongly fought off by French unions – are by far the most important reason for the rout of the Socialist Party in this year’s elections. Why would Macron fare any better when he begins to roll out his ‘reforms’, alongside the various other overtly business-friendly and austerity-driven ‘reforms’ on his agenda?

As Time magazine felt constrained to point out:

“There are already signs that Macron could face roiling anger in the months ahead, as he begins to roll out his sweeping economic reforms—including the record-low turnout in Sunday’s elections, and the fact that those same economic proposals sparked months of violent street protests just last year.

“Macron’s plans include cutting taxes for many businesses, and drastically overhauling France’s watertight labor protections, which he believes has paralyzed the labor market. He also wants to allow companies to negotiate their own deals with staff representatives, effectively breaking the power of national unions to dictate terms. In recent weeks Macron has hosted union leaders in the Elysée Palace, trying to stave off mass demonstrations against his plans.

“Despite these efforts, Macron could still face months of protests from union activists and far-left groups, who have depicted the former Rothschild banker as a metropolitan elitist representing only the interests of the rich (Vivienne Walt, ‘Emmanuel Macron built a revolution on hope. Now he has to face reality’, 19 June 2017). Ms Walt might also have mentioned that Macron is slashing public expenditure, reducing the number of public employees by 120,000, and committing France to spending 2% of its budget on Nato all the better to conduct wars of imperialist aggression, as demanded by the US ruling class.

These are all policies for which the French working class masses will be expected to pay.

As someone quite rightly commented: “The grapes of wrath are getting ripe”. We can expect France to become a powder keg of class warfare in the coming months and that it will turn out that in foisting Macron on the French people, the reactionaries have once again lifted a rock only to drop it on their own feet.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.