Part 3 (continued from previous issue)

In July there was a meeting in Birmingham of 60,000 when a prominent local reformer, Sir Charles Wolseley – not present – had been elected ‘legislatorial attorney’ for the city. This was part of a Radicals’ plan that every unrepresented city in Britain should send representatives to the House of Commons. Elections without the King’s Writ were illegal and a warrant for Wolseley’s arrest was promptly issued. On 21 July another vast meeting was held, at Smithfield Market. Hunt, the principal speaker, thought there were 70,000 – 80,000 present while Joseph Harrison (a self-styled ‘Revd’, who had come to the fore as a leading reformer in Stockport since Bagguley’s arrest), after travelling from Stockport to attend it, later told Bagguley there were150,000, while Hobhouse was assured there was only 10,000 present (a classic example of the message varying according to the sympathies and the agenda of the messenger, which will also be seen in the reporting of 16 August 1819 and which is still familiar to demonstrators today). Hunt produced a resolution which was adopted there which read: “That from and after the 1st day of January 1820, we cannot conscientiously consider ourselves bound in equity by any future enactments which may be made by persons styling themselves our representatives, other than those who shall be fully, freely and fairly chosen by the voices or votes of the largest proportion of the members of the State.” That would seem to indicate that Hunt was in favour of illegal elections such as that held at the Birmingham meeting (though later he denied it). Johnson clearly thought he was, suggesting that Hunt be ‘legislatorial attorney’ for London (though London had MPs), most probably wanting the nomination for the Manchester representative himself.

Lloyd had obtained approval from Hobhouse for a warrant for Harrison’s arrest for his part in the last Stockport meeting and Lloyd sent two of his special constables (being William Birch and one other) to London to report to the office of the Lord Mayor to ask for his assistance in arresting Harrison at the Smithfield meeting. This was done but only the powerful oratory of Hunt calling for restraint from the crowd prevented a major riot from breaking out in response to the arrest, carried out when the meeting was at its height and emotions most aroused. Hunt had good reason to be confident in his powers of crowd control.

These meetings caused concern in the government. Norris was already worried about the consequences of a Manchester assembly at which Hunt would be present. By a letter of 27 July, Hobhouse wrote to him: “On the subject of the expected meeting at Manchester on Monday, I have now to acquaint you that the Attorney and Solicitor General have given their opinion that the election of a Member of Parliament without the King’s Writ is a high misdemeanour and that the parties engaged and acting therein may be prosecuted for a Conspiracy”, adding that a meeting for such a purpose would be an unlawful assembly and it would be a matter of prudence and expediency for the magistrates to decide “on the spot” whether or not to disperse it. The encouragement of Hobhouse for the local magistrates to use the Manchester meeting as a chance to nip these developments in the bud could hardly have been clearer.

On 24 July the two special constables, William Birch and his companion, had arrived back in Stockport with Harrison as their prisoner. Harrison was to be lodged in Birch’s own house. Later, as Birch walked to the house of the Magistrate, Mr Prescott, he was surrounded by an angry crowd, including the secretary of the Stockport Reform Society with whom Harrison lodged. Another member of the crowd (never identified) pulled a gun and shot Birch. Birch was not injured beyond a powder burn to his cheek but the result was the spreading of wild rumours of riot and insurrection. Sidmouth had earlier that month called on the Lords Lieutenant of Lancashire, Cheshire and Warwickshire to put their Yeoman Cavalry on the alert, fearing civil disturbance after the mass meetings. The Earl of Derby, the Lord Lieutenant of Lancashire, had accordingly spoken to Thomas Trafford, commander of the new Manchester Yeomanry Cavalry, whose response was to order that his regiment’s swords be sharpened, ready for action. The Revd Hay, veteran chief magistrate of Salford, formerly the scourge of the Luddites, was now seriously unwell and left for a holiday away from the town, leaving the indecisive Norris in charge, with a new man as the chairman of the select committee of magistrates, to the concern of Hobhouse.

On July 31 the Manchester Observer announced that the meeting in St Peter’s Field would take place on the 9th (not the 2nd) of August. The advertisement gave clear notice of the purpose of the meeting, which was: “to take into consideration the most speedy and effectual mode of obtaining Radical Reform in the Common House of Parliament” and “to consider the propriety of the ‘Unrepresented Inhabitants of Manchester’ electing a person to represent them in Parliament” (our emphasis).

The magistrates immediately met to consider their response in the light of the advice of Hobhouse to Norris. Hobhouse had said: “if the meeting is not convened for the unlawful purpose, the illegality will not commence until the purpose is developed”, the unlawful purpose being an unauthorised election such as at Birmingham. The magistrates in their panic did not observe that the meeting was advertised to be to “consider”, but not to effect an election. They immediately authorised the appearance throughout the town of large posters headed “ILLEGAL MEETING” in banner type. The posters read: “Whereas it appears by advertisement in the ‘Manchester Observer’ of this day, that a PUBLIC and ILLEGAL MEETING is convened for Monday the 9th day of August next, to be held on the AREA, NEAR ST. PETER’S CHURCH, in Manchester; We, the Undersigned Magistrates, acting for the Counties Palatine of Lancaster and Cheshire, do hereby Caution all persons to abstain AT THEIR PERIL from attending such ILLEGAL MEETING”. The Notices provoked outrage on the streets and several unfortunate beadles who were given the task of posting up the Notices had their heads beaten as a result. Hobhouse realised the magistrates’ mistake regarding the legality of the meeting (the unfortunate wording of the notice, which actually warned people not to “abstain … from attending” rather than not to attend! was of less concern). To Sidmouth, returning to the Home Office from sick leave at that point, the notion that the magistrates would have acted other than in accordance with the strict letter of the law was an anathema and accordingly he instructed Hobhouse to write to the magistrates in his name, requiring them to reconsider their decision and to remind Norris how unfortunate it would be if, at the meeting, the magistrates ordered violence to be used: “it will be the wisest course to abstain from any endeavour to disperse the mob, unless they should proceed to acts of felony or riot”. Hobhouse, however, remained convinced, like Lloyd, that the workers should be shown a firm hand, and Sidmouth was once more leaving affairs in Hobhouse’s hands while he, Sidmouth, again retreated to the seaside for the sake of his health.

The panic of the magistrates can be understood in the light of events in and around Manchester during July. The workers in Manchester and in all the nearby towns were preparing for their big day when they would march to St Peter’s Field for the meeting to hear Orator Hunt. There were meetings most evenings when the workers would practise their marching. Some wanted to (and did) practise with weapons as well, but the leaders from the reformers were generally against that. Hunt was adamant that the workers should take no arms or weapons of any description with them to the meeting, not even for self defence, wanting to give the authorities no pretext for using force against the workers. Samuel Bamford, responsible for bringing one of the largest contingents, from Middleton, was also firm upon the point. He planned to have his contingent – upwards of 5,000 men, with women and children also – led by two ranks of the best-looking and best-dressed young men in their Sunday best white shirts and neckerchiefs, bearing branches of laurel to indicate their peaceful intent, followed by the banners and then the band, before the masses came behind in orderly ranks of 5 abreast. On 3 August, notices had been posted in and around Manchester informing the people of a ban on drilling imposed by the magistrates. The practising continued, however.

On 7 August, 1819, the Manchester Observer carried its second announcement of the meeting intended for St Peter’s Field. This time the date was fixed for 16 August and the purpose was redefined (to ensure legality) as: “To consider the propriety of adopting the most LEGAL and EFFECTUAL means of obtaining a REFORM in the Commons House of Parliament”, with no mention of any election. The meeting was scheduled for 12 o’clock, Henry Hunt was named as Chairman and Major Cartwright as one of the prominent reformers invited to attend. As with the earlier notice, over 700 householders were named as signatories, most of them hand-loom weavers. One result of the magistrates’ ill-considered ban of the 9 August meeting was a further week’s delay and even more publicity for the meeting. No-one in the neighbourhood of Manchester could now be unaware of the great event planned for 16 August. Hunt, however, was not told of the change and as a result arrived in Stockport on 8 August ready for a meeting the next day, and a great deal of persuasion was required to stop him turning round and going back to London right away. He was persuaded to stay with Johnson until the 16th and on the 9th he made a triumphant entry into Manchester through dense crowds of people gathered to see and to welcome him.

Another result of the week’s postponement was the absence from duty, in the run-up to and on 16 August, of the main men in charge of law enforcement, Lord Sidmouth and Sir John Byng. Revd Hay came back from his rest at his home on the other side of the Pennines to consult with Norris and agreed with Norris (with an indecisiveness not at all in keeping with his earlier actions against the Luddites) that it would be ‘inexpedient’ to issue a warrant for Hunt’s arrest but did not agree any course of action other than ‘wait and see’, and Hay then took a back seat, leaving it to Norris and the new chairman of the magistrates, William Hulton, to manage matters on the 16th. Sir John Byng was looking forward to attending the York Races as a guest of the Lord Lieutenant of the West Riding with a group of aristocratic fellow guests, and to seeing his favourite horse compete on 14 August, as a test for its run in the classic race, the St Leger at Doncaster, the following month. There had been no conflict between duty and pleasure when the meeting was scheduled for the 2nd and then for the 9th of August, but now he was faced with a stark choice, as he could not be in York on the 14th and at the same time be preparing his troops for the 16th, or even be present in Manchester on the 16th, without having to bow out of the party at the races altogether. He opted to go to the races, and in correspondence with Sidmouth he cited his many pressing “business affairs” as keeping him away from Manchester on the 16th. Byng left his second-in-command, Lieutenant Colonel Guy L’Estrange (another veteran of Waterloo but without Sir John’s wide experience) in charge of the troops, but Byng did not agree any plan for overall command to be vested in his subordinate, nor did he agree with the magistrates any plan of action in advance of the event. This was a critical omission. Everything was left to chance and to the local magistrates’ decisions on the day, with devastating results. This was in stark contrast to the preparations for the Blanketeers’ meeting of 2 March 1817 when Byng had assumed command of the militia as well as of the regular troops; a plan was agreed between the civil and military authorities, which on the day was carried out to the letter with virtually no casualties. Lord Sidmouth went back to the seaside to resume his convalescence, leaving in charge Hobhouse, who instructed all letters from the magistrates and spies to be sent directly to him henceforth and not to Sidmouth.

Norris called out the Cheshire and Manchester Yeomanry, which would be his to command on the day, and wrote to Sidmouth on 11 August (though Sidmouth was not in his office to receive it): “What the result will be God only knows. The day can scarcely be expected under such circumstances to pass in peace – although the revolutionaries will affect to wish it. The order of the day with them will be peace but many of them I have little doubt will come armed”.

Monday, 16 August, 1819

St Peter’s Field

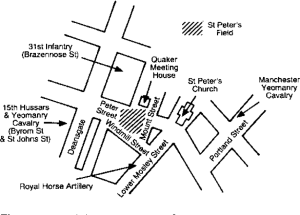

Manchester’s Boroughreeve in 1819 was Edward Clayton. He was determined that anything that might be used as an impromptu weapon should be removed from the Field and accordingly sent Thomas Worrell, Assistant Surveyor of Paving, on to St Peter’s Field at 7.00am to inspect the ground and arrange for ‘about a quarter of a load of stones’ to be carted away. The Field was in part a construction site, as Peter Street was planned to cross it from east to west, and there were trenches already dug for drainage across part of the southern half. It was an irregular quadrilateral, about 170 yards by 150 yards across at its broadest points. Down its eastern side ran Mount Street, where the magistrates would gather to observe the meeting from a second-floor room; Windmill Street ran along the southern boundary, with houses on the other side of the street from the Field, and the northern boundary was mainly bordered by the 10 foot high wall of the Quakers’ burial ground (the level of which behind the wall was over 6 feet higher than the level of the Field), with their Meeting House behind it (that wall being the only clearly recognisable feature remaining to this day, the Field long since having been built over). Some logs for building were piled by this wall. The western side was broken up by 3 streets running west from the Field, with the western part of Peter Street in the middle. The Field itself was flat and open and was still called ‘The Green’ by older residents, as was many a village green, though in August 1819 it was baked brown and dusty after weeks of hot, dry weather. No other enclosed area in the north of England was comparable: it had the capacity to hold 150,000 people without discomfort.

Around Manchester

Although the Field was deserted at 7.00am, activity had started in the surrounding towns, where marchers had begun gathering before dawn, in order to set off on their walk to Manchester in good time to arrive before the meeting was due to start at 12 noon. Some had several hours’ walk in front of them and may have supplied themselves with staves as walking sticks to help them along the way, as is customary with those used to walking long distances. However, the ban on any other item that could be used as a weapon was repeated to every group, never more emphatically than by Samuel Bamford, who marshalled his well-rehearsed contingent from Middleton behind their laurel branches, bands and specially-made, colourful banners. The banners were of locally woven silk and had the legends ‘Unity and Strength’, ‘Liberty and Fraternity’, ‘Parliaments Annual’ and ‘Suffrage Universal’. When the Middleton group met those from Rochdale, they were 10,000 strong combined; Bolton was sending another 10,000 and Saddleworth sent 3-5,000 behind a banner calling for ‘Equality or Death’. The pits at Macclesfield were found to be empty of miners that morning: they had gone to Manchester. With such a large number behind him, Samuel Bamford fully expected to find his way barred and to be turned back; but neither he nor any other group met any obstacle and all were allowed to proceed to Manchester and to gather on St Peter’s Field.

One of the by-products of the new technology was the employment of women in the factories, as brute strength was no longer a requirement of the work, and many women were included among the marchers – a first step along the long road to equality, although they were jeered by some by-standers and suffered a greater number of injuries, proportionate to their numbers, than the men. Bagguley from his prison cell had written a letter of encouragement to the Stockport Female Union and they sent an all-female delegation of marchers to the Field that day, as did the Oldham and Royton Female Unions. The Royton women marched behind a banner reading: ’Let us die like men, and not be sold like slaves’. Children were also present as the workers treated the day as a holiday. The hand-loom weavers could take a day off work as they pleased, being self-employed, or employed as piece-workers and not by the week, but the factory workers had formed the habit of taking a day off some Mondays after working a six- or seven-day week (such irregular days off being nick-named ‘saints’ days’); a practice not approved but not punished by their employers.

The Meeting

Estimates of the numbers present when all were assembled varied from 30,000 (the magistrates) to 150,000 (Hunt), with a local reporter estimating 120,000, on the Field and a further 40,000 in the surrounding streets. The upper figures are likely to be nearer the mark, given the number of towns sending contingents, the size of those contingents, the size of the Field and the eyewitness accounts in the press of people both in the Field itself and also in the streets.

The sight of all the people walking through the street of Manchester and converging on St Peter’s Field greatly alarmed the tradesmen and gentry of the town. The magistrates met at 9.00am before going to their observation post at the house in Mount Street, on the south-east of the Field, but were still undecided as to what they should do. The previous evening L’Estrange had been requested by the magistrates to put his troops on the alert and the Manchester and Cheshire Yeomanry had already been mobilised separately. Byng had earlier arranged for two horse-drawn cannon of the Royal Artillery to be brought to the town and they had been drawn through the streets the day before, then positioned in a street to the east of the Field. L’Estange had already stationed troops in all the surrounding towns as well as in Manchester; in Manchester he moved his troops into position early in the morning of 16 August, well before the marchers arrived on the streets. He chose to station his own cavalry (2 squadrons of the 15th Hussars) in Byron Street, a quarter of a mile to the west of the Field, in order to be near at hand if required, with foot soldiers from the 31st Foot and 88th regiment – over 500 men – variously positioned further away from the Field. The Cheshire Yeomanry (420 men under their second-in-command Lt Colonel Townshend) and some of the Manchester Yeomanry (under the manufacturer Capt Withington) were positioned with him in Byron Street; the remainder of the Manchester Yeomanry (under their CO Major Thomas Trafford, another manufacturer) was over half a mile away on a street beyond the eastern side of the field and out of touch with him. The final group, which, with the Manchester Yeomanry, was under the sole command of the magistrates, was the band of special constables. They were volunteers recruited and led by Nadin, the only full-time, paid constable, and were chosen for their strength and distinguished by the large metal badges they wore and the thick staves they carried. Nadin had been instructed by Clayton that the specials were to be the first forces of law and order on the Field that day. In all, there were more than 1,000 troops and 400-500 special constables available to Lt Col L’Estrange that day, but, critically, not all were directly under his command.

Before the speakers arrived, the Boroughreeve, Edward Clayton, had taken several hundred special constables onto the Field, forming them into two lines leading from the house holding the magistrates to the two wagons lashed together on the southern edge of the Field, by Windmill Street, which formed the temporary hustings. The reporter from the London Courier had decided to stick by Clayton that day, and he later reported that as the Boroughreeve pushed through the crowd with the special constables, using them to form a passageway for communication between the hustings and the magistrates, at no time had that officer made any suggestion that the meeting was illegal. The siting of the hustings proved unfortunate, for the wagons were downwind of the Field that day, with the result the Hunt’s words were blown away from the crowd and only the few thousand nearest to him could hear what he said. His pleas for calm could have no effect.

At 11.30am the open carriage bringing Hunt to the Field set off from Johnson’s cottage. It was full, with, in addition to Hunt and Johnson, James Moorhouse, the Stockport reformer, John Saxton, editor of the Manchester Observer, Richard Carlile, pamphleter, John Knight, veteran campaigner and, on the driver’s box, Mrs Mary Fildes, President of the Manchester Female Reform Union, with her committee of women, all dressed in white, ready to walk behind the carriage. Bamford’s 10,000 passed by and the carriage set off, intending to follow them, but, on getting separated in the crush in the streets, the carriage took a different route to the Field. On their way, John Tyas, the reporter from The Times of London begged a lift and was given permission to hang onto the side of the carriage and later to mount the hustings with the speakers. Hunt could see the advantage of getting coverage in the national as well as the local press.

As Hunt arrived at the Field, a great shout went up. As he approached the hustings, the bands struck up ‘See the Conquering Hero Comes’, followed by ‘God Save the King’, to prove their loyalty. The watching magistrates counted 18 banners and 5 ‘Caps of Liberty’ along the line taken by Hunt to approach the hustings. The banners’ slogans included, as well as those of Middleton and Royton already referred to, Saddleworth’s black banner proclaiming ‘Taxation without representation is tyrannical; equal representation or death’ and another saying ‘Union is strength – Unite and be free’. These were intended as messages of encouragement for Hunt, but (together with the numerous ‘Caps of Liberty’) were read by the magistrates as sinister warnings of violence to come. As Hunt mounted the hustings there were more loud cheers. All the occupants of the carriage joined Hunt on the hustings. But “so successful had been John Lloyd’s policy of arrest that not a single working-class leader of standing had been left free to speak” on 16 August (Robert Reid, The Peterloo Massacre, Heinemann, London, 1989). Johnson introduced Hunt and Hunt began to speak. But for all his oratorical experience, only the few thousand closest to him could hear what he said. 100 yards away in their first-floor room, the magistrates could hear the voice but could distinguish none of the words and were left to guess their import by the reaction to them of the listeners.

The magistrates had made no plan, save that if violence erupted which Nadin and the specials could not control, then they would call in the military. As the crowd outside increased, and well before the meeting began, however, over 60 manufacturers came to ask the magistrates to take action to forestall any such eruption. The magistrates’ chairman, William Hulton, already had taken the first steps even before Hunt was in full flow, by asking one of the two Chief Constables to instruct Nadin to arrest Hunt, Johnson, Knight and Moorhouse on the Field. The Chief Constable replied that without military assistance he could not do so without endangering the lives of Nadin and the specials, as there was now a wall of bodies surrounding the hustings. Hulton then wrote two notes. One, addressed to Thomas Trafford, the CO of the Manchester Yeomanry stationed to the east of the Field, read: “Sir, as chairman of the select committee of magistrates, I request you to proceed immediately to no.6, Mount Street, where the magistrates are assembled. They consider the Civil Power wholly inadequate to preserve the peace. I have the honour & c. Wm Hulton”. He wrote in similar terms to Lt Col L’Estrange, assembled with his cavalry and the rest of the Yeomanry, several streets away from the west of the Field, in Byron Street.

Subsequently Hulton explained his actions on the grounds that he considered “at that moment that the lives of all the persons in Manchester were in the greatest possible danger. I took this into consideration, that the meeting was part of a great scheme, carrying on throughout the country. We had received undoubted information upon that point, of the existence of such a scheme.” There undoubtedly was a scheme for a national campaign for reform of Parliament, but for mass meetings, not for revolution, at least not on the part of the leaders of the reform movement still at liberty. If the magistrates indeed had had such information of a scheme of sedition before the 16th, one can only wonder why they did not arrest the speakers before they reached the Field and turn back all the marchers before they reached Manchester, as they undoubtedly had the forces available to do so and had had plenty of opportunity before the people were assembled? It seems more likely that they simply lost their nerve on the day when they saw the size of the crowd and in the face of the pressure from the manufacturers’ requests for action. Many observers later wrote of their impression that the workers were treating the day as a holiday and the mood was more one of attending a celebration than planning an insurrection.

Once the letters were sent, the circumstances of the blocked streets meant that the letter to Thomas Trafford arrived first and his section of the Manchester Yeomanry was first on the scene; the positioning of the two troops of mounted men meant that the two groups were bound to act independently. Immediately on receiving the letter, their CO, Thomas Trafford, ordered his Yeomanry to draw their swords and they galloped straight for Mount Street, which was but a short and direct journey from their position. The first casualty of the day was a two-year-old boy, struck and killed instantly by a passing horse as his mother carried him across the road after, she thought, all the horses had passed. The Yeomanry stopped by the house where the magistrates were gathered while Nadin went onto the Field to instruct his specials to pull back and let the Yeomanry through to the hustings. Belatedly, the magistrates now decided to read the Riot Act. According to that law, an assembly became unlawful if it did not disperse within one hour of the Riot Act being read. However, they did not go on the Field to do so, as had (properly) been done by the then Boroughreeve on the day of the Blanketeers’ meeting in 1817, but instead (purportedly) one magistrate, Revd Ethelston, leant out of their first floor window and shouted it out to the crowd from above, with Revd Hay, the most senior magistrate present, swearing the he was right behind and heard every word. That was according to the magistrates’ account, but the Revd Stanley, vicar of St Peter’s, observing the scene from the room directly above the magistrates’, later reported that while he could hear a voice, as close as he was, he could not distinguish a word that was said. No-one from the people assembled on the Field reported having heard it and it is not to be expected that they could hear it from that distance and above the noise of the crowd, no matter how loud it was proclaimed. It would be farcical if not so serious. That was the only basis upon which the magistrates could claim to have acted lawfully, however (even though they had not observed the requirements of the Act by waiting for one hour for the crowd to disperse peacefully after the reading of the Act), as there was never any suggestion of any unlawful acts by anyone in the crowd before this point. Nadin came back to the magistrates and the Boroughreeve, with the two Chief Constables, prepared to go on the Field, leading the Yeomanry, to make the arrests. Hunt had spotted the disturbance as members of the crowd nearest the horses began to scatter and the Yeomanry responded to an order from their CO and raised their swords. Hunt called for and got a great cheer from the crowd. The Yeomanry responded by putting their spurs to their horses. It was 1.40pm. It took twice as long for the magistrate’s other messenger to reach L’Estrange, owing to the congested streets, but he was able to advise L’Estrange as to the best route to take in order to reach the Field. But even as L’Estrange was leading his troops towards the Field, it was apparent from the shouts and screams that could be heard coming from the Field that violent activity had already begun. The Revd Stanley was well placed to see what happened and he confirmed later that he saw no sign of any wrongdoing or disturbance prior to the intervention of the Manchester Yeomanry.

There are many and detailed accounts of the day’s events from eye witnesses among the on-lookers, those attending the meeting, and the law enforcers. The first eye-witness accounts appeared in the newspapers over the following days, in Manchester, in the surrounding towns, and in London, as many reporters were present. In 1820 there were the trials of the speakers and the evidence of witnesses given at those trials, extensively reported at the time (and the transcripts later printed in the compendium State Trials in 1888). There was also in 1820 the inquest into the death of one demonstrator killed on the Field (the nearest to a public inquiry into the events of 16 August, even it was adjourned part-way through and never resumed) and in 1821 an unsuccessful private prosecution for assault against some of the Manchester Yeomanry. It was the first such event to be so thoroughly observed and comprehensively reported and recorded.

Edward Clayton and the two Chief Constables were intent on leading the combined civil and military force to arrest Hunt and the others, but the undisciplined riders of the Manchester Yeomanry soon overtook them and Nadin, holding the warrant, also found himself following the horses. As the Yeomanry moved down the passage opened up by the specials, they increased their speed to a canter and the Revd Stanley, observing from the room above the magistrates, saw a woman’s body left on the ground behind the horses, the second casualty of the day. Insults were thrown at the Yeomanry and the horses then appeared to be out of control of their riders, as neither were trained in crowd control and were maddened or frightened respectively by the noise surrounding them. Some of the specials were alarmed at the approach if the horses and raised their truncheons, possibly as a means of identifying themselves. But they were not recognised as public officers by the Yeomanry and several were struck down by the horses or the flat swords. The Yeomanry drove their horses through the wall of people surrounding the hustings, while those in their path fled if they could. Hugh Birley was the first to reach the hustings and declared that he had a warrant to arrest Hunt. Hunt replied that he would surrender to the civil officer who could show him the warrant; by then Nadin had reached the hustings and could oblige. The others named on the warrant were not found immediately, apart from Johnson, who was also arrested. Nadin was struck on his arm by a brick and, according to Tyas, at the same time mayhem broke out around the hustings, with the Yeomanry shouting “Have at their flags!” and driving their horses towards both the banners on the hustings and those in the midst of the crowd. The lunging of the horses provoked a shower of bricks and stones and the Yeomanry then began chopping at the crowd with their swords, completely losing all control of their tempers. Thaxton, of the Manchester Observer was recognised and targeted but fortunately escaped with only his clothes slashed. Others were not so lucky: one man had his nose taken off by a sabre; a young woman was found bleeding on the ground and was pulled to safety in a nearby street. One Manchester woman recognised a Yeoman who raised his sword to her and cried out his name, saying that surely he would not strike her, whom he knew of old, but he struck, nevertheless.

The bright blue uniforms of the Manchester Yeomanry were now lost in the sea of outraged people and through the dust raised by the horses the magistrates could only see that, alongside the swords, sticks were raised, bricks were thrown, horses had stumbled and troopers had fallen. This was the situation when L’Estrange reached the Field with his disciplined cavalry and the Cheshire and remaining Manchester Yeomanry. He asked the magistrate Fulton what they wanted him to do and the response was “Good God, Sir! Do you not see that they are attacking the Yeomanry! Disperse the crowd!”. Orders were then given and the Cheshire Yeomanry formed a line along Windmill Street, behind the hustings, while the Hussars formed a line at right angles to the Yeomanry, in front of the magistrates’ gathering place in Mount Street. Both lines moved forward, driving the crowd before them west (where the streets off were rapidly blocked) and north (towards the wall forming the Quakers’ boundary) with the flat of their swords, inflicting more casualties as they went. It could hardly be otherwise. A junior Hussar later noted that the Field “in all parts was so filled with people that their hats seemed to touch”. Wellington once observed that anyone could get 10,000 men into a space but it needed a general to get them out again. On the Field that day there were at least ten times 10,000 men, women and children, but no competent general. The Manchester Yeomanry, as locals, and wearing bright blue uniform jackets, were the most easily recognised of all of the cavalry on the Field as well as the first on, and many were the stories of the injuries they inflicted, both by their sabres and by the collision of horse and human (see Reid ibid. for more of these individual stories).

By the time the combined cavalry had cleared the Field, there was a pile of bodies against the Quakers’ boundary wall, the iron railings in front of the houses in Windmill Street had been pushed to the ground under the weight of bodies seeking to escape the horses, many of the houses neighbouring the Field had opened their doors to fleeing and injured demonstrators, and the same junior Hussar, returning to the Field, noted that it was strewn with the bodies of those killed or too injured to move and was covered with hats, shoes, scarves, other items of clothing and musical instruments. The press of people in the narrow side streets leading from the Field meant that the carnage was hardly less there than on the Field itself. It was to be many weeks before a reasonably accurate estimate of the numbers killed and wounded was to emerge. This was when local benefactors set up a fund to compensate the wounded and the families of the dead and people felt able to come forward with their accounts, many having previously been wary of making known their presence at the meeting, for fear of repercussions. At that stage the figures were put at 11 killed and 420 wounded; very far from the figure of 63 admitted to the Manchester Infirmary on the 16th and 17th (of whom 3 died) reported to Lord Sidmouth by Revd Hay on the 19th when the latter travelled to London post haste after the massacre, eager to put the magistrates’ case to the government before too many adverse reports reached London. The following week, Hulton wrote to Sidmouth, saying that the total of 70 injured was “proof of the extreme forbearance of the military in dispersing an assemblage of 30,000”. The demonstrators’ injuries were recorded as cuts and blows by sabres as well as crushing and trampling injuries. Of the law enforcers, one special constable died at the hands of a member of the Manchester Yeomanry who mistook him for a demonstrator, and 70 of the various cavalry received minor injuries from sticks and stones, only one of them being severely injured by such impromptu weapons.

The Aftermath

Within a couple of hours of the forcible break-up of the meeting on 16 August 1819, rioting broke out in Manchester, and returning demonstrators started riots in the surrounding towns. Peace was only restored after the Riot Act was properly read and the troops intervened. It was 19 hours before peace was restored to Manchester, the magistrates having ordered that all shops should remain closed on 17 August. Within 24 hours eye-witness reports appeared in two London papers, sent by two local men – a reporter and a radical manufacturer – who together had seen Tyas, of the London Times, being arrested and taken to prison and had agreed that they should send reports to two different London papers without delay. Other papers were not slow to follow. It was the Manchester Gazette, printed the following Saturday, which gave the events the name ‘Peterloo’. After reading news of the massacre, the liberal and progressive members of the bourgeoisie were indignant. Meetings were organised all over the country to protest. Sir Frances Byrdett MP wrote a letter to his constituents in Westminster (later widely published in the Press) that he was “filled with shame, grief and indignation at the account of the blood spilled in Manchester … What, kill men unarmed and unresisting and Gracious God! women too, disfigured, maimed and trampled upon by dragoons!” On 2 September he appeared before a meeting of 30,000 alongside fellow reformers Major Cartwright and John Cam Hobhouse (cousin to Henry in the Home Office and an MP who later supported an attempt by Byrdett in the House of Commons to get a motion passed in favour of holding a public enquiry into the massacre). As a result of his speaking at this meeting, Byrdett was prosecuted for seditious libel, fined £5,000 and imprisoned for 3 months in 1820. A petition was started (by the Manchester manufacturer who was one of the initial reporters of the massacre) to protest against the events of 16 August and the rigged meeting organised by the magistrates on 19 August when a resolution had been passed in support of their actions. The petition obtained 2,480 signatures in three days. Shortly before he died, on 12 September 1819, from wounds sustained at ‘Peterloo’, John Lees, an Oldham clothworker and veteran of Waterloo, told a friend “At Waterloo it was man to man, but there it was plain murder!”

However, Lord Sidmouth secured the support of the cabinet, and the government then backed Sidmouth’s support for the actions of the magistrates, the yeomanry and the military and his programme for even greater repression to counter the widespread and swelling unrest and criticism of the authorities’ actions on 16 August. Within a few days of the massacre, Sidmouth himself wrote to congratulate the magistrates for their actions and he organised a letter from the Prince Regent to the Lords Lieutenant of Cheshire and Lancashire praising the efforts of their Yeomanry. But Sidmouth and the government failed to call out Sir John Byng for his gross dereliction of duty on 16 August, protected the direct perpetrators of the massacre from criticism or punishment, arrested, tried and imprisoned the speakers on the hustings on 16 August for sedition, defeated the calls for a public enquiry into actions of the law enforcers on 16 August 1819, and passed the notorious ‘Six Acts’, which removed/restricted still further the right of working men (and reformers) to meet, organise or communicate with each other, as well as imposing taxes on newspapers which made them unaffordable by the working class. It should not be surprising that the working class were at first angry at the events on the Field, then cowed and demoralised after the ruthless persecution of even the most peaceful and prominent of the reformers left them with no leaders. In addition to Byrdett (MP and baronet), Hunt, Bamford, Johnson, Healey and Knight were convicted of seditious assembly, while the others arrested on the hustings were released without charge – Tyas after a day, but the others after weeks and months in solitary confinement. The protests were suppressed; the radicals were not able to organise; the workers went back to work; the economy improved with a cyclical upswing; and industrialisation proceeded relentlessly, so that handloom weavers (whose suffering had been so severe and who had played so prominent a part in the reform movement in the period 1810-1819) had been consigned to history by the time a young Friedrich Engels wrote his first work The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844.

Parliamentary Reform

The government in 1819 was not afraid of losing office as a result solely of adverse public opinion, as, without reform, they had the tiny electorate sufficiently under their control, as well as the backing of the monarch (the Prince Regent, who became George IV in 1820). But the prosecutions and the legislative programme of severe repression showed that they were nervous about the possibility of serious civil unrest, which might have threatened the government, or at least the ruling party’s hold on power. The repression meant that the working class and the radical reformers were no longer a threat after 1820: all the prosecutions of that year (conducted in York and Leicester, at a safe distance from the industrial centres of Lancashire) passed without protest, the inquest into the death of John Lees was adjourned then aborted, and the private prosecution of members of the Manchester Yeomanry for assault failed. In the end it was the manufacturing bourgeoisie who had the clout – through their increasing wealth and their resulting support among the bankers and merchants – to bring about parliamentary reform. Eventually (13 years later) they had enough influence to persuade the Whigs (the opposition party in 1819, who came to power on the death of George IV in 1830) to enfranchise them and their new centres of industry by means of the Representation of the People Act of 1832 – the first, greatest Reform Act. That Act got rid of the rotten boroughs and re-organised all the constituencies so that parliamentary representation in the House of Commons reflected the population, in the process recognising and allotting MPs to the new industrial towns for the first time. However, the 1832 Reform Act did not grant universal male suffrage, or anything like it. Voting rights were given to male householders with property having a minimum annual value of £100 (down from £300), increasing the electorate from 217,000 to 345,000; but MPs were still not paid and the property qualifications for voters and MPs were only gradually reduced during the following 100 years. The wealthier manufacturers were enfranchised, however, and a succession of reforming Acts in their interests followed from then on: Acts to reduce customs levies on imported raw materials and exported manufactured goods, the Poor Law Reform Act, which abolished outdoor relief for over 80 years, Truck Acts to abolish payment in kind or by token, Factories and Mines Acts, to restrict the hours of work of women and children, and Local Government Acts to establish councils to run the new industrial towns (in which the manufacturers took the leading role) and the all-important Corn Law repeal, which made it possible for the cost of food (and hence wages) to be reduced (this bitterly opposed by the land-owning bourgeois).

The working class resumed the struggle for parliamentary reform with the Chartist movement in the middle of the 19th century. The communist movement, when that gradually came into being after 1848, always championed universal adult suffrage, although the other working class organisations did not include women’s suffrage in their demands before 1918 (hence the suffragist and suffragette movements of the late 19th and early 20th centuries). However, it was not until 1918 (the fourth Reform Act) that universal male suffrage (at 21 years) was introduced and women (over 30 and subject to a property qualification) were first given the right to vote. The Act of 1918 owed much to the pressure exerted on the ruling class by the Great October Revolution of the previous year, when the new, revolutionary government, had immediately granted universal and unconditional suffrage to all adults, men and women alike. Adult female suffrage was granted in Britain only in 1928 and the sixth Reform Act of 1969 lowered the voting age here from 21 to 18 years. Bernard Shaw, dramatist and Fabian (affiliated to the Labour Party when that was formed) said that “if voting changed anything, they’d abolish it”. By the time universal suffrage was granted in Britain, the bourgeoisie was confident that giving the working class the vote would not lead to the revolutionary overthrow of the bourgeois state. There were by then sufficient working class leaders bribed by position and privilege to be firmly attached to the ruling class and the status quo – proved by their supine support of ‘their’ bourgeoisie in the inter-imperialist war of 1914-18 and their leading the workers to become cannon-fodder in that war – to render that risk a small one.

The massacre on St Peter’s Field did not change the political landscape of Britain immediately in terms of the reform movement, contrary to the assertions of some of those commemorating these events today. It caused shock waves initially which led only to increased repression in the short term, and in the long term it became a folk memory. ‘Peterloo’ was not forgotten by the working class, but economic issues took centre stage together with the struggle for the right to unionise. Howard Spring (1889-1965), in his novel Fame is the Spur (1940), shows his hero using the memory of ‘Peterloo’ to give himself credence as a working-class radical and socialist, by using a sabre captured by his grandfather on St Peter’s Field as his signature at public meetings and calling himself ‘Shawcross of Peterloo’. (NB It is a novel still worth reading for its depiction of social democracy and the corruption of the leadership of the working class.)

Bagguley, the working class hero of the period, declared himself to be “a revolutionary, a republican and a leveller”. But 1819 was in the historical period of the bourgeois revolution. Civil unrest or a civil war might have led to the overthrow of the monarchy, but it would not have led to the overthrow of the bourgeoisie: at most a re-adjustment between sections of the bourgeoisie, which occurred anyway some 12-15 years later. It was not possible in 1819 for the newly emerging proletariat in Britain to lead a revolution or seize state power; they could only have been the foot soldiers for a section of the bourgeoisie. The workers then did not have the numbers or the experience, nor did they have the muscle of a revolutionary party to give strategic as well as tactical leadership. Nearly a century later, the working class of Russia was as small if not smaller in numbers, but rich in the experience of their fellow workers of Europe and under the leadership of a revolutionary Marxist party. The period of the proletarian revolution was still in the future – after the work of Marx, Engels and Lenin and the example of the Paris Commune had provided both theory and practice for the rising, revolutionary working class.

‘Peterloo’ was not a failure by the working class in their long struggle for emancipation and liberation. It was an early step along the way. It was the first such mass confrontation between workers and the forces of the state, though not the first time the full force of state power had been used against them. It would not be the last time they would be confronted with the force of the bourgeois state. Before industrialisation, peasants who rebelled were met by the army as well as having their leaders executed. After industrialisation, the Luddites were executed. After ‘Peterloo’ striking miners were met by troops (Tonypandy) and armed and mounted police (Orgreave). These are just a few examples of the unalterable fact that state power, in the hands of whichever class is the ruling class at the time, is based upon force – armed, military force as well as legal coercion. The lesson of ‘Peterloo’, as of all such episodes, is that the working class can never be truly emancipated or liberated from wage slavery until it wields state power.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.