By Sopiko Japaridze

Reproduced from Monthly Review, with thanks (posted Dec 15, 2023)

“If you’re not careful, the newspapers will have you hating the people who are being oppressed, and loving the people who are doing the oppressing.”—Malcolm X

A couple of years ago, I was hanging out with friends and decided to play a game. It resembled Mafia night but involved “Who is Hitler?” cards. We deal the cards, someone receives the Hitler card, and we have to figure out their identity through conversation. It’s a spin on the classic ‘Mafia’ game popular in Georgia. The ‘good guys’ were the ‘liberals,’ featuring a crest reminiscent of the Soviet Union—minus the hammer and sickle, which was replaced by a dove. The game pitted the liberals against the villainous fascists. None of the young participants knew about the Soviet Union’s central role in the defeat of fascism in the Second World War. This game, along with various forms of large and subtle propaganda, contributes to the distortion and rewriting of Soviet history since the collapse of the USSR. This narrative is reinforced through influential individuals, stories, narratives, holidays, books, films, and non-governmental organizations, among others.

I too had been influenced by anticommunist history. The Soviet Union had been often depicted as an immense, inhumane state, indifferent to its citizens—a portrayal reminiscent of the dystopian novels ingrained in our education since middle school in the United States. In addition, I had been ‘trained’ in anticommunist socialist circles in the United States and understood the USSR as a failed project (each tendency I was a part of marked different years as the betrayal of the revolution). However, upon returning to Georgia from the United States, where I had migrated during the wars and violence in the 1990s, I discovered a different perspective.

Georgian locals everywhere emphasised how the current state neglects its people, contrasting it with the care during the Soviet Union era. Even anticommunist liberals would reference Soviet standards and studies to oppose incessant construction and environmental damage during protests I attended. They recalled how, during the Soviet Union, constructing buildings higher than a certain level was deemed detrimental to people’s health, emphasising factors like sunlight and stable ground. Stringent regulations were in place to protect citizens.

My exploration of mining towns in Georgia revealed a stark reality. Residents showed me apartments covered in burned coal, children inhaling ashes on playgrounds. Initially, I was tempted to connect this to a perception of Soviet neglect for people in favour of industry output, but the residents vehemently objected. In the USSR, they explained, strict regulations prevented coal-burning near residential areas, and today’s common practice of open storage was illegal back then. They insisted that the current problems were nonexistent in the Soviet period.

Tragically, many preventable deaths have been caused by post-Soviet mining practices. Multiple mine explosions have taken lives, and interviews with miners have revealed a disturbing truth. The specific area witnessing frequent explosions in recent years was sealed off during the 1970s under the USSR, following a prior explosion. No mining was allowed there because it was deemed too dangerous. However, the private company that owns it today unsealed the area, leading to fatal consequences. These deaths were entirely preventable—a result of negligence in pursuit of easy access to coal.

In the gold-mining town of Kazreti, residents painted a grim picture of their current life. At first, I assumed that the town’s status as a mining hub from the USSR era might explain their sense of boredom, overwork, and exposure to high pollution, but the locals described life as more vibrant during the Soviet Union. They reminisced about lively nightlife, abundant sporting events, and the ability to travel affordably to Tbilisi and across the Soviet Union. Sports held a significant place in their community, with various events constantly taking place—from small towns to large cities. Technical colleges in these towns brought diversity and additional residents, creating a dynamic social fabric.

According to the residents, people were not only socially active but also physically healthier and stronger during the Soviet era. They highlighted the provision of extra food and nutrients to each worker, acknowledging the challenges of mining on the body. Food and nutrition were paramount concerns, with dedicated efforts to ensure proper nourishment for both workers and children. This contrast between the past and present underscored the significant changes in the town’s quality of life over time.

In the manganese-mining town, miners endure exhausting twelve-hour shifts, in contrast to the Soviet era, where stringent regulations limited work to seven hours, recognising the adverse impact on the body after extended periods in the mines. This protective measure aimed to prioritise the well-being of the workers is undermined today and the quota system incentivises long working days. One miner’s wife said, “They want us to meet the quotas like in the Soviet Union but they don’t give us any perks and benefits of the Soviet Union.”

One worker who is responsible for detonating the coal mines recounted a traumatic incident that cost him an arm. He revealed the painfully slow response time of paramedics, who took a whole hour to arrive. The subsequent journey to the nearest hospital, now distantly located due to hospital closures linked to privatisation, extended the ordeal by additional hours. The erosion of occupational health and safety standards during post-Soviet liberalisation emerged as another distressing pattern in my conversations.

This formerly vibrant town has now morphed into a landscape of unsafe mining, pollution, and a community forced into desperate measures. Residents are resorting to manganese drilling in their own backyards, underscoring the dire economic circumstances and the degree of pollution. The collapse of other once-thriving industries besides mining has left the town grappling with the consequences of unbridled privatisation profoundly impacting the well-being and safety of its inhabitants.

The role of occupational disease specialists has been reduced to being merely symbolic since the radical liberalisation of the 2000s. This period is marked by the total destruction of labour and social institutes, bans on progressive taxation, and criminalisation of communism and communist symbols. During the Soviet Union, approximately two hundred diagnoses of occupational illnesses were made each year. However, in recent years, there have been no diagnoses. The director of the last remnants of the Institute of Occupational Specialists revealed that she made two diagnoses a few years ago and faced threats from the company for doing so. This once-vital institution, now defunct, holds decades of research on labour safety and conditions, unable to share its old findings, conduct new research, or diagnose people.

The director candidly stated, “You are going to think I’m crazy, but the best occupational health and safety was under communism.” I reassured her that I didn’t consider her crazy. Struggling with the loss of their professional purpose and fueled by a connection to their identity through work, these specialists gather in a dilapidated building to drink coffee and talk about the past.

But there are those with a different view of history of Georgia and the Soviet past, both locals and foreigners who engage in nuanced, evidence-based conversations about the Soviet Union. Primarily, they came to address history projects triggered by exaggerated hyper-nationalist narratives. Unfortunately, these discussions struggle to penetrate the dominant communication channels even though the population is willing and ready for more nuanced discussions about the USSR.

A significant number, if not the majority, of those who grew up in the Soviet Union harbour a positive, if not outright affectionate, view of this past. Yet, these sentiments are often marginalised and dismissed by prevailing propaganda in Georgia. Whenever someone attempts to share positive aspects of the Soviet Union, they cautiously glance around to ensure their words don’t attract unwanted attention. Over the decades, individuals expressing such sentiments have endured criticism from liberals and conservatives united in anticommunism who dismiss their feelings as mere ‘nostalgia,’ treating them like naive children.

The prevailing anti-Soviet narrative in Georgia acts like an enchanting spell, affecting everyone, with nuances and facts seemingly reserved for the professionals or the marginalised population who are locked apart. Meanwhile, experts and academics possess the potential to counter the destructive hyper-nationalist narratives, particularly in the context of current Georgia. Given that the propaganda is supported by institutions, grant funds, state-sponsored memory politics, international and regional organisations, among others, it is understandable that they are reluctant to jeopardise their status in this enchanted circle. Let’s face it: academics aren’t renowned for their bravery. This is where we, as socialists, must step up to the challenge.

While it has been common for Western socialists to publicly distance themselves from the Soviet Union (‘No, we aren’t those kinds of socialists!’), the critical task of updating Soviet Union history based on both old and new realities persists. It is also important to analyse the experiences of people who lived through it, as well as the ramifications that followed, rather than just the cherry-picked memoirs weaponised during the Cold War.

The Soviet Union posed the biggest danger to capitalism because it symbolised a real-life, evangelising vision of another world being possible—a concept that now frequently feels like an empty protest slogan. Even if the initiative failed in the USSR at various points, its existence inspired even more audacious utopian projects elsewhere.

The Soviet Union was a major material sponsor of decolonisation, and its disappearance is felt around the world. Today, the dominant development narrative provides no alternative, reinforcing a duality of core and periphery in relationships. This gap affects literature, art, music, and interpersonal relationships as well as geopolitics. Former Soviet citizens are separated, with no opportunities or means to reconnect, and the Third World no longer overlaps with the once-dominant Soviet presence. The current scenario sees post-Soviet elites connected only to Europe, cleaving themselves from the rest of the common people.

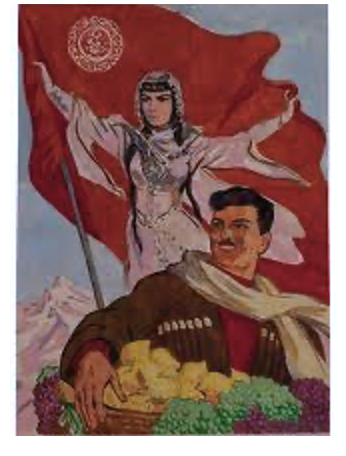

There are countless successful experiments within the USSR that are worth revisiting and reviewing despite the reduction of the Soviet experiment to violence and repression in the popular imagination. It is only fitting that the memory of the Soviet Union is increasingly demonised and distorted, evident in newly coined days like Black Ribbon Day and the unjust comparisons to fascism throughout Europe. Importantly, the countless fighters—like my grandfathers—who sacrificed their lives to defeat fascism are being wrongly equated to fascists themselves. Fascism, which originally emerged as an opposition to socialism, has paradoxically been reframed to be historically opposed to liberalism instead of its bedfellow.

The reduction of discussions about the Soviet Union to mere nostalgia is a consequence of a deeper issue. More robust and nuanced discussions about the USSR are unfortunately now confined to the realm of experts. When individuals find themselves unable to leverage their wealth of knowledge and to contribute to the reconstruction of a new society—perceived as relics from the past waiting to fade away—the only refuge becomes private conversations with friends and colleagues. This isolation from active participation in shaping the future leaves them confined to sharing memories and insights in smaller, more personal circles. It reflects a broader challenge of integrating the wisdom and experiences of the past into the ongoing narrative of societal progress.

In response to their marginalisation, Soviet nostalgists—the often-disenfranchised members of society—resist through the private preservation of the USSR’s memory. With their knowledge and experiences pushed to the sidelines, this becomes a subtle act of defiance. It is a way to uphold a vision of the past that holds more than mere nostalgia; it is a quiet protest against being relegated to the fringes of society. It is their unspoken assertion of value in shaping the narrative, even if confined to the interpersonal. Countless Facebook groups and pages are dedicated to reminiscing about the better times in the USSR. A sentiment often echoed is ‘Tbilisi used to be a relationship,’ capturing the essence of the compassion between people in the capital of Soviet Georgia. It wasn’t just a geographical location; it was a genuine and caring connection, a stark contrast to the present day.

People often surrender their power by believing they possess none. The fear of communism and its potential to mobilise people for a transformative world is evident in the continuous enactment of anticommunist laws during the capitalist restoration. Despite thirty years of efforts to bury and vilify its memory, the resilience of communism remains undefeated. The enduring struggle reflects the underlying apprehension among proponents of capitalist ideologies who recognise the enduring power and appeal of a vision that challenges the status quo. Socialists shouldn’t dismiss the entire Soviet experiment as a failure. Recognising the imperative to redefine Soviet Georgia beyond mere nostalgia, Bryan Gigantino and I launched the Reimagining Soviet Georgia podcast. Our goal is not to consign Soviet Georgia to the past but to invigorate it, making it a dynamic force in shaping new visions for the world. The podcast seeks to inspire, rescuing the Soviet era from vilification and unfounded associations with fascism. We advocate for a shift beyond academic discussions and adding another front besides reminiscing about the Soviet past solely around the dinner table.

About Sopiko Japaridze

Sopiko Japaridze is the chair of Solidarity Network, a health and care worker union in Georgia, and host of the history podcast Reimagining Soviet Georgia.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.