On 27 October the long-running dispute between the Spanish central government and the regional Catalan government came to a head, with the central government suspending Catalonia’s autonomous regional government for persisting in unconstitutional activity and the latter, unconstitutionally, declaring itself to have seceded and formed an independent sovereign state.

On 27 October the long-running dispute between the Spanish central government and the regional Catalan government came to a head, with the central government suspending Catalonia’s autonomous regional government for persisting in unconstitutional activity and the latter, unconstitutionally, declaring itself to have seceded and formed an independent sovereign state.

Demonstrations rallying hundreds of thousands of people held over the past few months in support of Catalan separatism, together with the willingness of a large section of the Catalan popular masses, as well as the Catalan police force, to flout the central government’s attempts to ensure that the unconstitutional referendum called for 1 October this year be not held and to resist the violence unleashed by the Guardia Civil, indicate that the central government is facing a losing battle in trying to force its will on Catalonia.

The bourgeoisies of other European countries look on in amazement at the sheer cack-handedness of the way Spain’s central government has handled the problem. While it is true that the Spanish constitution states unequivocally that Spain is indivisible (implying that any attempt at secession of any part of its territory would be unconstitutional and illegal), recent events have shown that the constitution is flawed as, far from being an instrument of peace and reconciliation, it is proving to be a hindrance to the search for a creative solution to the problems that have arisen.

“Things could have been so different, so easily, starting with the Popular Party restraining the vindictive impulse that drove it to overrule the autonomy statute [a negotiated and agreed compromise making concessions to Catalan regional demands, especially in the area of fiscal autonomy] through the courts. Even if it had not, the massive street protests two years later provided another opportunity. Had Rajoy possessed an ounce of statesmanship, he could have gone to Barcelona, made a conciliatory speech and offered dialogue with the less militant, more pliable Catalan government that was then in power. Applause would have rung out around the hall and the Puigdemont radicals would probably have been done for.

“The dangerous showdown today between Spanish fanatics and Catalan romantics would never have happened if, along with the change in mood music, the upshot of talks had been the granting of a binding referendum such as the one Scotland was given three years ago. Catalans say of themselves that two emotions vie in their hearts, seny and rauxa: common sense and raging passion. They are by ancient Mediterranean tradition a trading nation. When they are not angry, as they are now, they are the most practical people on earth. A proper referendum held a couple of years ago would have yielded in all likelihood a substantial “no” to independence from Spain and, as happened in Quebec, the subject would have been put to bed for a generation at least.

“Instead what we have is the cruel absurdity of the Madrid government acting towards the Catalans like a husband who hates his wife and mistreats her but refuses to let her contemplate leaving him, screaming ‘She’s mine!’” (John Carlin, ‘Catalan independence: arrogance of Madrid explains this chaos’, The Times, 7 October 2017).

Even a referendum held this year is unlikely to have yielded a vote for separation, as opinion polls had consistently been saying that a majority of voters opposed it. This was demonstrated in last year’s parliamentary election where a majority of votes went to non-separatist parties. Unfortunately the single party with the largest number of votes was able to form a government, and it pursued its separatist agenda ruthlessly despite being, or maybe even because of being, a minority administration.

The rise of Catalan nationalism

Although Catalonia was forcibly annexed to Spain in 1714, and its bourgeoisie was subjected to all kinds of discriminatory measures for a long period of time, with attempts to eradicate Catalan culture and the use of the Catalan language having been made from time to time, most recently under the Franco dictatorship, nevertheless, after 1978 when the autonomous Catalan regional government was restored, along with language rights, etc., the overwhelming majority of Catalans were happy to be Spanish as well as Catalan. In 2006 the pro-independence vote stood at barely 15 per cent of the population simply because the outrageous injustices of the Franco era had been reversed. But since 2006, the pro-independence sentiment appears to have embraced more and more people, having reached a peak of 48% at the end of 2016. What has been the cause of that?

The most important cause of seismic shift in people’s consciousness has of course been the outbreak of the world economic crisis of overproduction which rocked the whole financial system to its foundations in 2007. The ensuing bank bailouts gave rise to austerity, just as the crisis of overproduction was causing massive job losses, with consequent inability to pay mortgages and loss of homes on a mass scale. In Spain this gave rise to significant unrest in the form of the Indignados movement and the rise of the leftist populist political party Podemos to challenge the traditional parties of government in Spain, i.e., the conservative Partido Popular and the social-democratic Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE) as a threat to Spain’s career politicians. These developments were not at all to the liking of the Spanish bourgeoisie, including the Catalan bourgeoisie, which hastened to look for ways to divide the working class movement, in particular by using regional nationalism.

The result in Catalonia that separatist organisations which, when in power in the Catalan autonomous regional government had happily slashed spending on health and education, set themselves up as champions of the Catalan people against the Spanish central government which it blamed for their own austerity drive. The divisive idea was spread that “Madrid” was overtaxing Catalonia in order to squander Catalonia’s hard earned money on supporting the lazy ne’er-do-wells of Andalucía and other less prosperous parts of Spain. It has to be said to the credit of the people of Catalonia that more than half of them have refused to swallow this bait. They are, however, a largely silent majority because of their fear of reprisals and abuse from fired-up nationalists. But on 8 October they took to the streets of Barcelona in their hundreds of thousands, promoting the slogan We are Catalan and Spanish. One participant from Tarragona interviewed by The Times said:

“You see how many people really oppose independence. The independence people are better mobilised than us and we never raise our voices because we are frightened of reprisals at work or in the street. But now it is vitally important to show Catalonia is part of Spain. I am for dialogue to sort this out. Perhaps they could give the Catalans control over taxes, because they always complain that Madrid takes all the money” (see Graham Keeley, ‘Spanish loyalists on the streets to defy Catalan breakaway’, 9 October 2017).

The Catalonian separatist bourgeoisie had hoped that on secession the Catalan state would remain in the European Union, as part of the ‘responsible’ northern European élite, rather than the ‘profligate’ southern countries which have borne the brunt of the financial crisis – Portugal, Italy, Greece and Spain. The EU authorities have, however, made it clear that this will not happen, with the result that the Catalan bourgeoisie is rapidly moving the headquarters of its various enterprises out of Catalonia into other parts of Spain. First to leave were the Catalan banks Sabadell and La Caixa, but there has been a positive stampede of over 1,000 businesses departing even before the unilateral declaration of independence, and one can expect hundreds more to be packing their bags in the next few weeks. These companies do business and make profits throughout Spain, not just in Catalonia, and they will continue to pay their taxes to the Spanish government. Their departure will cause thousands of job losses in the region.

In fact, separation of Catalonia, while damaging to Spain as a whole, will on many counts be far worse for the Catalan people, even if the Spanish government belatedly discovers some wisdom and desists from unleashing a civil war – a vain hope, unfortunately. Quite apart, then, from the backlash from a bone-headed Spanish central government, the following adverse consequences for the Catalan people arise from the setting up of a separate Catalan state, as explained by Wolfgang Munchau in the Financial Times of 9 October 2017 (‘A Catalan breakaway would make Brexit look like a cakewalk’);

“…Independence really means third-country status — Catalexit.

“In that case, Catalan citizens would lose their Spanish and EU citizenship because that privilege exists only in conjunction with the citizenship of a member state. … The border between Spain and Catalonia would become a heavily guarded external border of the EU and the Schengen zone of passport-free travel. Catalans would have to apply for visas if they want travel to Spain or the EU. As a non-member of the World Trade Organization, Catalonia would have no automatic right to reduced WTO tariffs. What would make Catalan independence much worse than the most extreme version of Brexit would be the region’s immediate forced exit from the eurozone.

“Catalexit would constitute a dramatic sudden return of the eurozone crisis. The banking system in one of the world’s wealthiest regions could collapse. This is why two Catalan banks decided last week to shift headquarters to Spain. They want to ensure continued access to funding by the European Central Bank and the Bank of Spain. Catalonia could, in theory, emulate the example of Montenegro, and unilaterally adopt the euro as its currency. But Montenegro is a tiny country with gross domestic product of just over €3bn. Catalonia’s GDP was €224bn last year, larger than Portugal’s. Catalonia is also unprepared to introduce its own currency on independence day. It would be mad to try to run such a large developed economy without a central banking infrastructure. Extricating yourself from the EU is difficult enough, as we can see with the UK. To extricate yourself from a currency union at the same time is an economic suicide mission. The single strongest argument against Catalan independence at this stage is an utter lack of preparation. I would go further and argue that the presence of a monetary union makes a regional independence movement impossible.”

Paradoxically, what will save the day for the Catalan people so that they are not hit by the consequences spelt out by Wolfgang Munchau is the fact that Spain will never accept the validity of any attempt at secession by Catalonia which will therefore remain, as far as the EU is concerned, fully part of Spain and, therefore, of the EU.

In the meantime, the central government has provisionally suspended the Catalan autonomous government with a view to the region holding elections for new regional government in December. In Spain as a whole the Catalan question has diverted attention away from the horrors of the economic crisis that the Spanish people continue to suffer, so what appears to outsiders to be Rajoy’s total lack of statesmanship, from the narrow and selfish point of view of his party, his own career and the Spanish bourgeoisie, amounts to tactical brilliance. The complicity of Rajoy and his party in corruption and fraud – forgotten. The docility of the non-Catalan working class in the face of austerity – ensured. The popularity of the Popular Party – restored! If the cost of this assuredly most temporary triumph is for the most prosperous region in Spain to become ungovernable and the unleashing of civil war, well, so be it!

“When Catalonia becomes independent, every Catalan city and town will erect in its central square a statue of Mariano Rajoy,” joked Agustin Gervas, a retired diplomat in Madrid. “Nobody has done more than him to promote Catalan independence”.

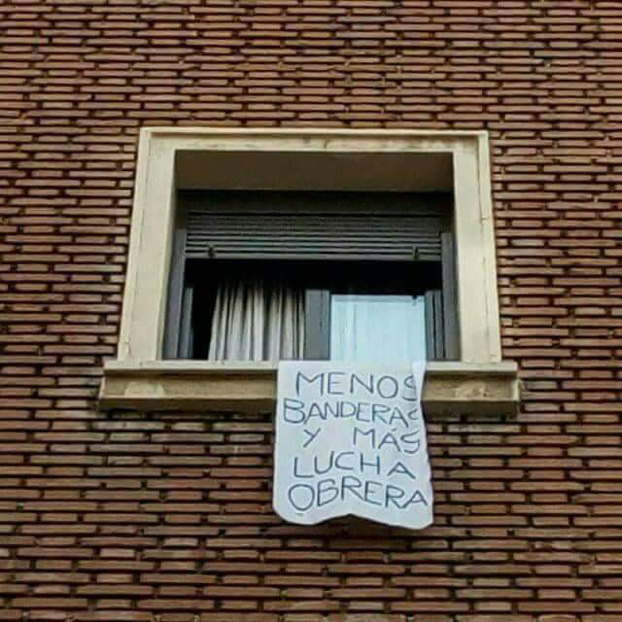

For our part, we endorse the slogan put forward by Spanish Marxist-Leninists – Menos banderas y más lucha obrera (fewer flags and more working-class struggle). This is the way forward for the Spanish proletariat, which must not allow itself to be diverted along the path of nationalism. The Spanish bourgeois government is the enemy of the entire Spanish working class, not just the Catalans, and the fight against capitalism requires unity, not nationalist division.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.