Last year, to mark the 100th anniversary of the start of the first imperialist world war, the CPGB-ML and Stalin Society held a series of meetings. The

purpose of these meetings was to refute the imperialist falsification of the meaning and essence of that war and to espouse the proletarian viewpoint and

to expose the hideous reality by cutting through bourgeois lies and obfuscations. In the September and November 2014 issues of LALKAR we published the

presentations made at a public meeting organised by the CPGB-ML at Saklatvala Hall in Southall on 9 August 2014 when Ella Rule, Deborah Lavin and Harpal

Brar made presentations concerning various aspects of the First World War. In this issue we reproduce the very substantial presentation on World War 1 and

the Irish national-liberation movement that Keith Bennett made to the Stalin Society on 20 July 2014 to coincide with the 99th anniversary of the Irish

Easter Uprising. It remains for a future issue to reproduce the excellent presentation made by Paul Cannon on the mutiny of British soldiers in France.

Last year, to mark the 100th anniversary of the start of the first imperialist world war, the CPGB-ML and Stalin Society held a series of meetings. The

purpose of these meetings was to refute the imperialist falsification of the meaning and essence of that war and to espouse the proletarian viewpoint and

to expose the hideous reality by cutting through bourgeois lies and obfuscations. In the September and November 2014 issues of LALKAR we published the

presentations made at a public meeting organised by the CPGB-ML at Saklatvala Hall in Southall on 9 August 2014 when Ella Rule, Deborah Lavin and Harpal

Brar made presentations concerning various aspects of the First World War. In this issue we reproduce the very substantial presentation on World War 1 and

the Irish national-liberation movement that Keith Bennett made to the Stalin Society on 20 July 2014 to coincide with the 99th anniversary of the Irish

Easter Uprising. It remains for a future issue to reproduce the excellent presentation made by Paul Cannon on the mutiny of British soldiers in France.

‘We serve neither King nor Kaiser but Ireland’ was the slogan that hung in front of Liberty Hall in Dublin following the outbreak of inter-imperialist slaughter in 1914. Today, Liberty Hall is the headquarters of SIPTU, one of Ireland’s leading trade unions. In the period covered by this presentation, it was the headquarters of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU), and it was the place of work of James Connolly, who coined this slogan and was responsible for the prominent place it was given.

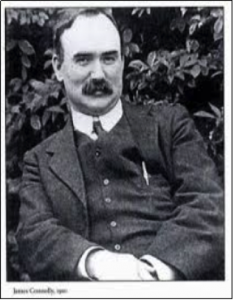

James Connolly was the revolutionary leader of the Irish working class, a great Irish patriot and a great Marxist. This presentation is based around his life and work.

Liberty Hall was where Connolly edited and published a succession of revolutionary newspapers and where he organised and trained the Irish Citizen Army.

The Irish Citizen Army had been formed by Connolly in 1913 to defend striking workers and their families in the Dublin Lockout – the longest, most significant and most bitterly-fought labour dispute in Irish history, which lasted from 26 August 1913 to 18 January 1914 and which centred on workers’ right to organise. Lenin proudly described the Irish Citizen Army as ‘the first Red Army in Europe’.

The significance and topicality of this presentation therefore rests on the following aspects:

Ÿ On the significance of the Irish national-liberation struggle against British imperialism. I am sure I do not need to remind many comrades here of these words written by Marx in 1870:

” After studying the Irish question for many years I have come to the conclusion that the decisive blow against the English ruling classes (and it will be decisive for the workers’ movement all over the world) cannot be delivered in England but only in Ireland ” (Letter to Sigfrid Meyer and

August Vogt by K Marx, 9 April 1870)

Ÿ As an example of the attitude and stance that the revolutionary working-class movement should take towards imperialist war, not only in words but, above all, in deeds. This is not simply a matter of observing a 100th anniversary out of academic curiosity. Nor even just of honouring a revolutionary leader – although Connolly and all the patriotic martyrs of Ireland’s long struggle for freedom are certainly worthy of the utmost honour and respect.

We live in dangerous times. Across the world, to cite just some examples of current conflicts and tensions making the headlines, in Nigeria, Libya, Palestine, Syria, Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan, Ukraine, the East and South China Seas, the Korean peninsula, and so on, we see not just localised or unrelated disputes, but grave events which, if they are not checked by national-liberation and proletarian revolutions, may well end in a third world war, likely to take the form of an attempted imperialist reconquest of China and Russia.

Nobody can say exactly how events may unfold, or what may ultimately provide the trigger for a wider conflict, just as nobody could tell in the years and months leading up to August 1914, but what we can say for sure is that the question of the attitude that socialists and the working-class movement should take to imperialist war and to the anti-imperialist struggle could scarcely be more timely.

The Basle Manifesto

In August 1907, the world’s socialist parties had met in conference in Stuttgart, Germany, and adopted a resolution, which concluded with these words:

“If a war threatens to break out, it is the duty of the working classes and their parliamentary representatives in the countries involved, supported by the coordinating activity of the International Socialist Bureau, to exert every effort in order to prevent the outbreak of war by the means they consider most effective, which naturally vary according to the sharpening of

the class struggle and the sharpening of the general political situation.

“In case war should break out anyway, it is their duty to intervene in favour of its speedy termination and with all their powers to utilise the economic and political crisis created by the war to rouse the masses and thereby to hasten the downfall of capitalist class rule.” (Resolution adopted at the Seventh International Socialist Congress of Stuttgart, 24 August 1907)

A further congress of the Second International was held in Copenhagen in 1910, in which, on the hard-fought insistence of Lenin, it was unanimously reiterated that, in the event of a war breaking out among the great powers, it would be an inter-imperialist war and that the duty of each working class and its party in such an eventuality would be to reject the imperialist war, reject ‘defence of the fatherland’, and for the working class to turn guns on its own bourgeoisie – to turn the imperialist war into a civil war.

The outbreak of war in the Balkans led to the convening of an extraordinary international socialist conference in the Swiss city of Basle in November 1912. The only questions discussed were those related to the threat of war. This conference unanimously adopted the Basle Manifesto.

Reiterating the basic principles set out in the Stuttgart and Copenhagen resolutions, the manifesto called on the people of all countries to oppose wars of aggression by every means and, in case war did break out, to utilise it to hasten the downfall of capitalist class rule. It also pointed out that the war that was brewing was of a predatory, imperialist, reactionary and slave-driving character, and that workers should regard participation in such a war as a crime – a criminal ‘shooting at each other for the profits of the capitalists, the ambitious dynasties’.

The Basle manifesto went on to warn the various bourgeois governments in the following terms:

“Let the governments remember that with the present conditions of Europe and the mood of the working class, they cannot unleash a war without danger to themselves. Let them remember that the Franco-German war was followed by the revolutionary outbreak of the Commune, that the Russo-Japanese war set into motion the revolutionary energies of the peoples of the Russian Empire . . . That is to say, it triggered the Russian revolution of 1905” (‘Manifesto of the International Socialist Congress at Basel’, 25 November 1912).

Lenin gave high praise to the Basle Manifesto, saying:

“Summing up, as it does, the enormous propagandist and agitational literature of all the countries against war, this resolution is the most exact and complete, the most solemn and formal exposition of socialist views on war and on tactics in relation to war” (VI Lenin, The Collapse of the Second International, June 1915).

Split in the working-class movement

Yet, less than two years after this manifesto was unanimously adopted by the representatives of world socialism, and within weeks of the outbreak of fighting at the end of July 1914, the vast majority of the workers’ parties forgot all about the solemn commitments they had given to their own and to the international working class, and were instead voting for war credits and for ‘defence of the fatherland’ – that is, for what was very soon to degenerate into the industrial slaughter of both working-class soldiers and civilians on an historically unprecedented scale.

It was against this epic and bloody historical canvas that the decisive breach – one that had been maturing and developing for a number of years – occurred between reactionary social democracy and revolutionary Marxism.

At first, as is so often the case, the forces of revolutionary Marxism, as compared to their opponents, were few in number. By far their most important contingent was the Bolshevik party led by VI Lenin. This party’s principled stand was, of course, to lead directly to the Great October Socialist Revolution of 1917, thereby profoundly altering the course of human history.

Among others taking a principled stand on this all-important question, Lenin once singled out Karl Liebknecht in Germany, Adler in Austria and MacLean in Britain for his approbation as ” the best-known names of the isolated heroes who have taken upon themselves the arduous role of forerunners of the world revolution” (see ‘The crisis has matured’, October 1917). To them should be added the revolutionary working-class movement in Ireland, led by James Connolly.

The world working-class revolution began with the action of individuals, whose boundless courage represented everything honest that remained of that decayed official “socialism” which is in reality social-chauvinism. Liebknecht in Germany, Adler in Austria, MacLean in Britain-these are the best-known names of the isolated heroes who have taken upon themselves the arduous role of forerunners of the world revolution

Irish Bolshevism and the Easter Rising

In stark contrast to almost all the major socialist parties of Europe, Connolly took an essentially Bolshevik approach to imperialist war. He not only worked to oppose it, to oppose British imperialism, but also to take the opportunity to strike a blow for Irish freedom – something which was to culminate in his central role in the Easter Rising of 1916.

With the full participation of the Irish Citizen Army, and with Connolly effectively as Commander-in-Chief, the Easter Rising was significant not only as a working-class insurrection, but also as an example of the revolutionary working class joining with revolutionary nationalism and revolutionary democracy in the national-liberation struggle.

In this way, too, Easter 1916 was a harbinger of some of the greatest events of the 20th century. They may well not have had any detailed familiarity with his work, but in a very real sense, the likes of Ho Chi Minh, Mao Zedong and Kim Il Sung stand in the Connolly tradition of waging the national-liberation struggle as the first stage on the road to socialism.

The Easter Rising was announced in the form of a proclamation of independence by a provisional government. The proclamation was signed by Connolly and six others. All seven signatories were to be executed by the British following the defeat of the rising, with Connolly being the last of them to face the firing squad.

This proclamation represented the united-front consensus of the leaders of the rising, but Connolly was instrumental in its drafting and it clearly reflected his advanced thinking.

Its main body read as follows:

“Having organised and trained her manhood through her secret revolutionary organisation, the Irish Republican Brotherhood, and through her open military organisations, the Irish Volunteers and the Irish Citizen Army, having patiently perfected her discipline, having resolutely waited for the right moment to reveal itself, she now seizes that moment, and, supported by her exiled children in America and by gallant allies in Europe, but relying in the first on her own strength, she strikes in full confidence of victory.

“We declare the right of the people of Ireland to the ownership of Ireland, and to the unfettered control of Irish destinies, to be sovereign and indefeasible. The long usurpation of that right by a foreign people and government has not extinguished the right, nor can it ever be extinguished except by the destruction of the Irish people. In every generation the Irish people have asserted their right to national freedom and sovereignty; six times during the last three hundred years they have asserted it in arms. Standing on that fundamental right and again asserting it in arms in the face of the world, we hereby proclaim the Irish Republic as a sovereign independent state, and we pledge our lives and the lives of our comrades-in-arms to the cause of its freedom, of its welfare, and of its exaltation among the nations.

“The Irish Republic is entitled to, and hereby claims, the allegiance of every Irishman and Irishwoman. The Republic guarantees religious and civil liberty, equal rights and equal opportunities to all its citizens, and declares its resolve to pursue the happiness and prosperity of the whole nation and all of its parts, cherishing all of the children of the nation equally and oblivious of the differences carefully fostered by an alien government, which have divided a minority from the majority in the past.

“Until our arms have brought the opportune moment for the establishment of a permanent national government, representative of the whole people of Ireland and elected by the suffrages of all her men and women, the Provisional Government, hereby constituted, will administer the civil and military affairs of the Republic in trust for the people” (Proclamation of the Irish Republic, 24 April 1916)

Although short, this is a profound document, perhaps comparable to South Africa’s Freedom Charter, for example, which was highly advanced in its progressive and socialist-oriented content, certainly for its day, but even for the present. Let’s just note:

· Ÿ The right of full ownership of the nation and its destiny is vested in the people as a whole.

· Ÿ The equality of men and women and full women’s suffrage are proclaimed, 12 years before the British state was to extend the franchise to all women over the age of 21.

· Ÿ Civil and religious liberty are guaranteed, with equal rights and equal opportunities to all citizens.

· Ÿ Happiness and prosperity are to be pursued for the whole nation and all of its parts.

· Ÿ Perhaps above all, the Republic is to cherish all the children of the nation equally.

Clearly therefore, James Connolly is central to our story.

Life of James Connolly

Interestingly, James Connolly was not actually born in Ireland, but, on 5 June 1868, in the Cowgate area of Edinburgh to Irish immigrant parents from County Monaghan. Connolly spoke with a Scottish accent throughout his life. His father and grandfathers were labourers and, after just a few short years of schooling, James, too, began his working life as a labourer at around the age of 10.

However, owing to grinding poverty, just as his elder brother John had done before him, Connolly enlisted in the British Army. He joined up at the age of 14, by giving a false name and lying about his age. He served in Ireland for nearly seven years, in which time his hatred of British imperialism steadily grew, and he deserted when he heard that his regiment was to be posted to India.

Connolly returned to Edinburgh and became active in the Scottish Socialist Federation, becoming its secretary in 1895. Connolly was also a founder of Britain’s Socialist Labour Party (the original one), which split from the Social Democratic Federation in 1903, and he also spent a period of time in the United States of America, during which he was variously a member of the Socialist Labor Party of America, the Socialist Party of America and the Industrial Workers of the World – the famous ‘Wobblies’ of Joe Hill fame.

He was thus a leading participant in the socialist movement in three countries and on two continents.

When the Easter Rising occurred on 24 April 1916, Connolly was Commandant-General of the Dublin Division and, therefore, as noted, seeing as nearly all the fighting during Easter Week took place in Dublin, he was effectively Commander-in-Chief of the rising.

As already mentioned, he was the last of the seven signatories of the proclamation to be executed, on 12 May 1916, in Dublin’s Kilmainham jail. Connolly had been badly injured in the fighting, and a doctor had already said that he had in any case no more than a day or two to live, but a vengeful British government insisted that the execution should go ahead.

As he was unable to stand, Connolly was transported by military ambulance to Kilmainham, carried to a prison courtyard on a stretcher, tied to a chair and shot. Along with the other leaders of the rising, his body was buried in a mass grave without a coffin.

Connolly as a Marxist

One of the most prominent Marxists of his day, Connolly is notable for his contributions on a whole range of questions – not only on the national question and on the revolutionary organisation of the working class, but also, for example, on women (he wrote that working-class women were the ‘slaves of slaves’), on revolutionary culture (he noted that a revolutionary movement should be considered a mere sect unless it was also characterised by the singing of revolutionary songs), on history (both of Ireland and of the working class), on religion, on military affairs (where he studied any examples he could find of urban warfare, in particular), and so on.

This self-taught working-class intellectual, whose formal schooling ended at the age of 10, was notable for his prodigious output on numerous topics. Going through his Collected Works, it is not uncommon to find several articles dated to the same day, although this may be in part explained by the publication dates of the various working-class newspapers he edited. But besides writing, Connolly was also building a working-class political party, a revolutionary trade-union movement, and the first Red Army in Europe – indeed, the world – as well as forging unity with the revolutionary nationalists. And he was doing all this while trying to support and provide for his family, often in conditions of grinding poverty.

It should be said that this great leader also had certain weaknesses – and, dialectically, they were often connected to his strengths. Connolly lived on a historical cusp, a moment of transition, whereby he was certainly a Marxist – indeed, we would say a very great Marxist indeed, but he was not fully a Marxist-Leninist – although, in fairness, that term was only to be formulated some years after his death.

Ÿ Connolly’s stand on the national question was undoubtedly one of his strengths. Indeed, its prescience echoes through the twentieth century and up to today. But he was not always fully scientific in his formulations. For example, his frequent reference to the ‘Irish race’ (and indeed to Hungarians, Finns, Jews and many others as ‘races’) now sounds somewhat anachronistic.

Ÿ As noted, in the US he worked closely with the Industrial Workers of the World and with Daniel De Leon’s Socialist Labor Party, and his views on working-class organisation could be closer to syndicalism than to Leninism.

Ÿ Connolly was also a religious believer and considered himself a Catholic to the end of his days.

But in any reasonable overall assessment from the standpoint of the working class, the biggest take-away has to be, in my view, just how advanced he was. And, above all, that, to employ Engels’ eulogy of Marx, ‘he was above all a revolutionist’, one, to borrow the words he spoke at his own court martial, who was prepared to attest to that with his life.

Opposition to the partition of Ireland

In the months leading up to the outbreak of war in Europe, much of Connolly’s attention was focused on the prospects of conflict at home. The Liberal government of Herbert Asquith had in 1912 introduced the third bill that would allow for home rule, a step short of full independence, for Ireland.

Even such a limited step was bitterly opposed by the most reactionary sections of society – by the Tory party and by the Irish unionists, led by Sir Edward Carson, who, on 13 January 1913 formed the Ulster Volunteer Force and threatened armed insurrection to forestall even modest reform in Ireland.

In the face of this, Asquith’s Liberals joined with the bourgeois Irish Parliamentary Party, led by John Redmond and Joseph Devlin, in proposing, supposedly as a temporary measure, the partition of Ireland.

It was a proposal to which Connolly was bitterly opposed. Published in the Irish Worker of 14 March 1914, as ‘Labour and the proposed partition of Ireland’, Connolly wrote that the proposals of Asquith, Devlin and Redmond, ‘reveal in a most striking and unmistakable manner the depths of betrayal to which the so-called nationalist politicians are willing to sink’.

He continued by unmasking the class basis of the religious bigotry of the Orange Order:

“Now, what is the position of Labour towards it all? Let us remember that the Orange aristocracy now fighting for its supremacy in Ireland has at all times been based upon a denial of the common human rights of the Irish people; that the Orange Order was not founded to safeguard religious freedom, but to deny religious freedom, and that it raised this religious question, not for the sake of any religion, but in order to use religious zeal in the interests of the oppressive property rights of rackrenting landlords and sweating capitalists. That the Irish people might be kept asunder and robbed whilst so sundered and divided, the Orange aristocracy went down to the lowest depths and out of the lowest pits of hell brought up the abominations of sectarian feuds to stir the passions of the ignorant mob. No crime was too brutal or cowardly; no lie too base; no slander too ghastly, as long as they served to keep the democracy asunder.”

He concluded this article with these highly prophetic words:

“Such a scheme as that agreed to by Redmond and Devlin, the betrayal of the national democracy of industrial Ulster would mean a carnival of reaction both North and South, would set back the wheels of progress, would destroy the oncoming unity of the Irish Labour movement and paralyse all advanced movements whilst it endured.

“To it Labour should give the bitterest opposition, against it Labour in Ulster should fight even to the death, if necessary, as our fathers fought before us.”

A carnival of reaction

A carnival of reaction, both North and South, indeed describes the result when British imperialism finally succeeded in partitioning Ireland in the 1920s. In April, 1963, when the then South African minister of justice, Belthazar Johannes Vorster (1915-1983), who later became prime minister in 1966, was introducing some new apartheid laws (The Coercion Bill) he publicly stated that he ” would be willing to exchange all the legislation of this sort for one clause of the Northern Ireland Special Powers Act” (cited by Peter Berresford Ellis in ‘Lest we forget – life in Northern Ireland before “the troubles”, on the www.irishdemocrat.co.uk website) , whilst in the south, anyone who wants to know what became of the Connolly pledge to cherish all the children of the nation equally needs only watch the 2002 film The Magdalene Sisters or the more recent Philomena (2013); or read the reports, in recent months, of the discovery of a mass grave containing the remains of nearly 800 babies in Tuam, County Galway (see ‘Tell us the truth about the children in Galway’s mass graves’ by Emer O’Tooler, guardian.co.uk, 4 June 2014)

Having been prepared to countenance partition, the next betrayal of Messrs Redmond and Devlin came as no surprise to Connolly. They supported the imperialist war, on the specious pretext that, by helping her to defeat her enemies, a grateful Britain would at last bequeath home rule to the Irish at its victorious conclusion.

To this Connolly responded with his article, ‘Our duty in this crisis’, published in the Irish Worker for 8 August 1914:

“What should be the attitude to the working-class democracy of Ireland in face of the present crisis? I wish to emphasise the fact that the question is addressed to the ‘working-class democracy’ because I believe that it would be worse than foolish – it would be a crime against all our hopes and aspirations – to take counsel in this matter from any other source.

“Mr John E Redmond has just earned the plaudits of all the bitterest enemies of Ireland and slanderers of the Irish race by declaring, in the name of Ireland, that the British government can now safely withdraw all its garrisons from Ireland, and that the Irish slaves will guarantee to protect the Irish estate of England until their masters come back to take possession – a statement that announces to all the world that Ireland has at last accepted as permanent this status of a British province. Surely no inspiration can be sought from that source.”

Connolly then proceeded to answer his question as follows:

“In the first place, then, we ought to clear our minds of all the political cant which would tell us that we have either ‘natural enemies’ or ‘natural allies’ in any of the powers now warring. When it is said that we ought to unite to protect our shores against the ‘foreign enemy’, I confess to be unable to follow that line of reasoning, as I know of no foreign enemy of this country except the British government and know that it is not the British government that is meant.

“In the second place, we ought to seriously consider that the evil effects of this war upon Ireland will be simply incalculable, that it will cause untold suffering and misery amongst the people, and that as this misery and suffering have been brought upon us because of our enforced partisanship with a nation whose government never consulted us in the matter, we are therefore perfectly at liberty morally to make any bargain we may see fit, or that may present itself in the course of events.

“Should a German army land in Ireland tomorrow, we should be perfectly justified in joining it if by doing so we could rid this country once and for all from its connection with the Brigand Empire that drags us unwillingly into this war.

“Should the working class of Europe, rather than slaughter each other for the benefit of kings and financiers, proceed tomorrow to erect barricades all over Europe, to break up bridges and destroy the transport service that war might be abolished, we should be perfectly justified in following such a glorious example and contributing our aid to the final dethronement of the vulture classes that rule and rob the world.

“But pending either of these consummations it is our manifest duty to take all possible action to save the poor from the horrors this war has in store.”

Clearly drawing on the memories of the Irish famine of the 1840s, as well as the general hunger that was still the lot of the working class, he continued:

“Let it be remembered that there is no natural scarcity of food in Ireland. Ireland is an agricultural country, and can normally feed all her people under any sane system of things. But prices are going up in England and hence there will be an immense demand for Irish produce. To meet that demand all nerves will be strained on this side, the food that ought to feed the people of Ireland will be sent out of Ireland in greater quantities than ever and famine prices will come in Ireland to be immediately followed by famine itself. Ireland will starve, or rather the townspeople of Ireland will starve, that the British army and navy and jingoes may be fed. Remember, the Irish farmer like all other farmers will benefit by the high prices of the war, but these high prices will mean starvation to the labourers in the towns. But without these labourers the farmers’ produce cannot leave Ireland without the help of a garrison that England cannot now spare. We must consider at once whether it will not be our duty to refuse to allow agricultural produce to leave Ireland until provision is made for the Irish working class.”

Connolly was quite clear as to what he was proposing. He went on:

“Let us not shrink from the consequences. This may mean more than a transport strike, it may mean armed battling in the streets to keep in this country the food for our people. But whatever it may mean it must not be shrunk from. It is the immediately feasible policy of the working-class democracy, the answer to all the weaklings who in this crisis of our country’s history stand helpless and bewildered crying for guidance, when they are not hastening to betray her.”

And lastly in this article, he situated this struggle as Ireland’s contribution to the wider, international struggle for socialism:

“Starting thus, Ireland may yet set the torch to a European conflagration that will not burn out until the last throne and the last capitalist bond and debenture will be shrivelled on the funeral pyre of the last warlord.”

A week later, in the 15 August 1914 edition of Forward, Connolly built on this internationalist theme, in his article, ‘A continental revolution’. For its passion and lucidity, for its excoriation of those who were now in the process of ripping up the solemn agreements they had signed up to in Stuttgart, Copenhagen and Basle, for its clear-sightedness on what needed to be done to stop the war, and for its brilliant handling of the relationship between patriotism and internationalism, I find myself with no alternative but to quote this short article in its entirety:

“The outbreak of war on the continent of Europe makes it impossible this week to write to Forward upon any other “question. I have no doubt that to most of my readers Ireland has ere now ceased to be, in colloquial phraseology, the most important place on the map, and that their thoughts are turning gravely to a consideration of the position of the European socialist movement in the face of this crisis.

“Judging by developments up to the time of writing, such considerations must fall far short of affording satisfying reflections to the socialist thinker. For, what is the position of the socialist movement in Europe today? Summed up briefly it is as follows:

“For a generation at least the socialist movement in all the countries now involved has progressed by leaps and bounds, and more satisfactory still, by steady and continuous increase and development.

“The number of votes recorded for socialist candidates has increased at a phenomenally rapid rate; the number of socialist representatives in all legislative chambers has become more and more of a disturbing factor in the calculations of governments. Newspapers, magazines, pamphlets and literature of all kinds teaching socialist ideas have been and are daily distributed by the million amongst the masses; every army and navy in Europe has seen a constantly increasing proportion of socialists amongst its soldiers and sailors, and the industrial organisations of the working class have more and more perfected their grasp over the economic machinery of society, and more and more moved responsive to the socialist conception of their duties. Along with this, hatred of militarism has spread through every rank of society, making everywhere its recruits, and raising an aversion to war even amongst those who in other things accepted the capitalist order of things. Anti-militarist societies and anti-militarist campaigns of socialist societies and parties, and anti-militarist resolutions of socialist and international trade union conferences have become part of the order of the day and are no longer phenomena to be wondered at. The whole working class movement stands committed to war upon war – stands so committed at the very height of its strength and influence.

“And now, like the proverbial bolt from the blue, war is upon us, and war between the most important, because the most socialist, nations of the earth. And we are helpless!

“What then becomes of all our resolutions; all our protests of fraternisation; all our threats of general strikes; all our carefully-built machinery of internationalism; all our hopes for the future? Were they all as sound and fury, signifying nothing? When the German artilleryman, a socialist serving in the German army of invasion, sends a shell into the ranks of the French army, blowing off their heads; tearing out their bowels, and mangling the limbs of dozens of socialist comrades in that force, will the fact that he, before leaving for the front ‘demonstrated’ against the war be of any value to the widows and orphans made by the shell he sent upon its mission of murder? Or, when the French rifleman pours his murderous rifle fire into the ranks of the German line of attack, will he be able to derive any comfort from the probability that his bullets are murdering or maiming comrades who last year joined in thundering ‘hochs’ and cheers of greeting to the eloquent Jaurès, when in Berlin he pleaded for international solidarity? When the socialist pressed into the army of the Austrian Kaiser, sticks a long, cruel bayonet-knife into the stomach of the socialist conscript in the army of the Russian tsar, and gives it a twist so that when pulled out it will pull the entrails out along with it, will the terrible act lose any of its fiendish cruelty by the fact of their common theoretical adhesion to an anti-war propaganda in times of peace? When the socialist soldier from the Baltic provinces of Russia is sent forward into Prussian Poland to bombard towns and villages until a red trail of blood and fire covers the homes of the unwilling Polish subjects of Prussia, as he gazes upon the corpses of those he has slaughtered and the homes he has destroyed, will he in his turn be comforted by the thought that the tsar whom he serves sent other soldiers a few years ago to carry the same devastation and murder into his own home by the Baltic Sea?

“But why go on? It is not as clear as the fact of life itself that no insurrection of the working class; no general strike; no general uprising of the forces of Labour in Europe, could possibly carry with it, or entail a greater slaughter of socialists, than will their participation as soldiers in the campaigns of the armies of their respective countries? Every shell which explodes in the midst of a German battalion will slaughter some socialists; every Austrian cavalry charge will leave the gashed and hacked bodies of Serbian or Russian socialists squirming and twisting in agony upon the ground; every Russian, Austrian, or German ship sent to the bottom or blown sky-high will mean sorrow and mourning in the homes of some socialist comrades of ours. If these men must die, would it not be better to die in their own country fighting for freedom for their class, and for the abolition of war, than to go forth to strange countries and die slaughtering and slaughtered by their brothers that tyrants and profiteers might live?

“Civilisation is being destroyed before our eyes; the results of generations of propaganda and patient heroic plodding and self-sacrifice are being blown into annihilation from a hundred cannon mouths; thousands of comrades with whose souls we have lived in fraternal communion are about to be done to death; they whose one hope it was to be spared to cooperate in building the perfect society of the future are being driven to fratricidal slaughter in shambles where that hope will be buried under a sea of blood.

“I am not writing in capricious criticism of my continental comrades. We know too little about what is happening on the continent, and events have moved too quickly for any of us to be in a position to criticise at all. But believing as I do that any action would be justified which would put a stop to this colossal crime now being perpetrated, I feel compelled to express the hope that ere long we may read of the paralysing of the internal transport service on the continent, even should the act of paralysing necessitate the erection of socialist barricades and acts of rioting by socialist soldiers and sailors, as happened in Russia in 1905. Even an unsuccessful attempt at social revolution by force of arms, following the paralysis of the economic life of militarism, would be less disastrous to the socialist cause than the act of socialists allowing themselves to be used in the slaughter of their brothers in the cause.

“A great continental uprising of the working class would stop the war; a universal protest at public meetings will not save a single life from being wantonly slaughtered.

“I make no war upon patriotism; never have done. But against the patriotism of capitalism – the patriotism which makes the interest of the capitalist class the supreme test of duty and right – I place the patriotism of the working class, the patriotism which judges every public act by its effect upon the fortunes of those who toil. That which is good for the working class I esteem patriotic, but that party or movement is the most perfect embodiment of patriotism which most successfully works for the conquest by the working class of the control of the destinies of the land wherein they labour.

“To me, therefore, the socialist of another country is a fellow-patriot, as the capitalist of my own country is a natural enemy. I regard each nation as the possessor of a definite contribution to the common stock of civilisation, and I regard the capitalist class of each nation as being the logical and natural enemy of the national culture, which constitutes that definite contribution.

“Therefore, the stronger I am in my affection for national tradition, literature, language, and sympathies, the more firmly rooted I am in my opposition to that capitalist class which, in its soulless lust for power and gold, would bray the nations as in a mortar.

“Reasoning from such premises, therefore, this war appears to me as the most fearful crime of the centuries. In it the working class are to be sacrificed that a small clique of rulers and armament makers may sate their lust for power and their greed for wealth. Nations are to be obliterated, progress stopped, and international hatreds erected into deities to be worshipped.”

Attitude to German imperialism

The next week Connolly responded to reports that the German socialist Karl Liebknecht had been shot and killed for his opposition to the war.

Liebknecht opposed the war but, in order not to break party discipline, he abstained in the 4 August vote for war credits in the Reichstag. On 2 December 1914, he was the only member of the German parliament to vote against further war credits in the second such vote, defying Karl Kautsky and another 109 of his own party’s members.

The news that Liebknecht had been murdered in August 1914 was obviously premature. Liebknecht went on to campaign against the war, was imprisoned for high treason, became a founder of the Communist Party of Germany, and, together with his comrade Rosa Luxemburg, led the January 1919 Sparticist uprising in Berlin, as a result of which they were both murdered by the social-democratic government, which was in league with militarists.

But Connolly’s reaction to these reports – which he himself acknowledged were unconfirmed at his time of writing – is once again worth quoting at length, as it elucidates his position, the revolutionary position, on imperialist war, and, inter alia, refutes the suggestion (just as does some of what I have already quoted) that is occasionally made that Connolly was somehow ‘pro-German’ in the conflict.

James Connolly’s ‘A martyr for conscience sake’ was published in Forward on 22 August 1914:

“Supposing, then, that it was true, what would be the socialist attitude toward the martyrdom of our beloved comrade? There can be little hesitation in avowing that all socialists would endorse his act, and look upon his death as a martyrdom for our cause. And yet if his attitude was correct, what can be said of the attitude of all those socialists who have gone to the front, and still more of all those socialists who from press and platform are urging that nothing should be done now that might disturb the harmony that ought to exist at home, or spoil the wonderful solidarity of the nation in this great crisis?

“As far as I can understand these latter, their argument seems to be that they did their whole duty when they protested against the war, but that now that war has been declared it is right that they also should arm in defence of their common country . . . We are told, for instance, that the same policy is being pursued by all socialist parties. That the French socialists protested against the war – and then went to the front, headed by Gustave Hervé, the great anti-militarist; the German socialists protested against the war – and then, in the Reichstag, unanimously voted 250 millions to carry it on; the Austrians issued a manifesto against the war – and are now on the frontier doing great deeds of heroism against the foreign enemy; and the Russians erected barricades in the streets of St Petersburg against the Cossacks, but immediately war was declared went off to the front arm in arm with their Cossack brothers. And so on. Now, if all this is true, what does it mean? It means that the socialist parties of the various countries mutually cancel each other, and that as a consequence socialism ceases to exist as a world force, and drops out of history in the greatest crisis of the history of the world, in the very moment when courageous action will most influence history.

“We know that not more than a score of men in the various cabinets of the world have brought about this war, that no European people was consulted upon the question, that preparations for it have been going on for years, and that all the alleged ‘reasons’ for it are so many afterthoughts invented to hide from us the fact that the intrigues and schemes of our rulers had brought the world to this pass. All socialists are agreed upon this. Being so agreed, are we now to forget it all: to forget all our ideas of human brotherhood, and because some twenty highly-placed criminals say our country requires us to slaughter our brothers beyond the seas or the frontiers, are we bound to accept their statement, and proceed to slaughter our comrades abroad at the dictate of our enemies at home?

“The idea outrages my every sense of justice and fraternity. I may be only a voice crying in the wilderness, a crank amongst a community of the wise, but whoever I be, I must, in deference to my own self-respect, and to the sanctity of my own soul, protest against the doctrine that any decree of theirs of national honour can excuse a socialist who serves in a war which he has denounced as a needless war, can absolve from the guilt of murder any socialist who at the dictate of a capitalist government draws the trigger of a rifle upon or sends a shot from a gun into the breasts of people with whom he has no quarrel, and who are his fellow labourers in the useful work of civilisation.

“We have for years informed the world that we were in revolt against the iniquities of modern civilisation, but now we hear socialists informing us that it is our duty to become accomplices of the rulers of modern civilisation in the greatest of all iniquities, the slaughter of man by his fellow man. And that as long as we make our formal protest we have done our whole duty, and can cheerfully proceed to take life, burn peaceful homes, and lay waste fields smiling with food!

“Our comrade, Dr Liebknecht, if he has died rather than admit this new doctrine, has died the happiest death that man can die, has put to eternal shame the thousands of ‘comrades’ in every European land, who, with the cant of brotherhood upon their lips, have gone forth in the armies of the capitalist rulers – murdering and to murder. The old veteran leader of German social democracy, his father, Wilhelm Liebknecht, said in one of his pamphlets:

“‘The working class of the world has but one enemy, the capitalist class of the world, those of their own country at the head of the list.’

“Well and truly has the son lived up to the truly revolutionary doctrine of the father: lived and died for its eternal truth and wisdom.”

Just and unjust wars

Connolly summed up the distinction between different types of war as follows:

“The war of a subject nation for independence, for the right to live out its own life in its own way may and can be justified as holy and righteous; the war of a subject class to free itself from the debasing conditions of economic and political slavery should at all times choose its own weapons, and hold and esteem all as sacred instruments of righteousness. But the war of nation against nation in the interest of royal freebooters and cosmopolitan thieves is a thing accursed.”

One of the things that particularly vexed Connolly was the war propaganda that claimed that the various protagonists, particularly Britain and Tsarist Russia, were somehow fighting for the rights of small nations. In ‘The friends of small nationalities’, published in Forward on 12 September 1914, he wrote about how

“the Russian government and the British government stand solidly together in favour of small nationalities everywhere except in countries now under Russian and British rule.

“Yet, I seem to remember a small country called Egypt, a country that through ages of servitude evolved to a conception of national freedom, and under leaders of its own choosing essayed to make that conception a reality. And I think I remember how this British friend of small nationalities bombarded its chief seaport, invaded and laid waste its territory, slaughtered its armies, imprisoned its citizens, led its chosen leaders away in chains, and reduced the new-born Egyptian nation into a conquered, servile British province.

“And I think I remember how, having murdered this new-born soul of nationality amongst the Egyptian people, it signalised its victory by the ruthless hanging at Denshawai of a few helpless peasants who dared to think their pigeons were not made for the sport of British officers.

“Also, if my memory is not playing me strange tricks, I remember reading of a large number of small nationalities in India, whose evolution towards a more perfect civilisation in harmony with the genius of their race, was ruthlessly crushed in blood, whose lands were stolen, whose education was blighted, whose women were left to the brutal lusts of the degenerate soldiery of the British Raj . . .”

He continued by saying that when the Irish press wrote about German atrocities against civilians in the course of conflict:

“I remember that in South Africa Lord Roberts issued an order that whenever there was an attack upon the railways in his line of communication every Boer house and farmstead within a radius of ten square miles had to be destroyed . . . I remember how the British swept up the whole non-combatant Boer population into concentration camps, and kept it there until the little children died in thousands of fever and cholera; so that the final argument in causing the Boers to make peace was the fear that, at the rate of infant mortality in those concentration camps, there would be no new generation left to inherit the republic for which their elders were fighting.

“This vicious and rebellious memory of mine will also recur to the recent attempt of Persia to form a constitutional government, and it recalls how, when that ancient nation shook off the fetters of its ancient despotism, and set to work to elaborate the laws and forms in the spirit of a modern civilised representative state, Russia, which in solemn treaty with England had guaranteed its independence, at once invaded it, and slaughtering all its patriots, pillaging its towns and villages, annexed part of its territories, and made the rest a mere Russian dependency. I remember how Sir Edward Grey, who now gushes over the sanctity of treaties, when appealed to, to stand by and make Russia stand by the treaty guaranteeing the independence of Persia, coolly refused to interfere.

“Oh, yes, they are great fighters for small nationalities, great upholders of the sanctity of treaties!

“And the Irish Home Rule press knows this, knows all these things that a poor workman like myself remembers, knows them all, and is cowardly and guiltily silent, and viciously and fiendishly evil.”

Connolly and the theory of people’s war

The British government did not dare to try and impose conscription on Ireland, at least not until it introduced legislation in 1918, but it was mooted repeatedly. In ‘The ballot or the barricade’, published in the Irish Worker of 24 October 1914, Connolly made clear what the response should be and in so doing developed the theory of guerrilla warfare, of people’s war:

“We of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union, we of the Citizen Army, have our answer ready. We will resist the Militia Ballot Act, or any form of conscription, and we begin now to prepare our resistance. Upon the Volunteers we urge similar resolves, similar preparations.

“Understand what this means. It means a complete overhauling and remodelling of all the training and instruction hitherto given to those corps. It means that the corps shall be taught how to act and fight when acting against an enemy equipped with superior weapons, instead of all teaching being based upon the ideas of British military textbooks, which always presume an equality of weapons, or even a superiority upon the British side. It means that much that has been taught will be worse than useless if acted upon, as such teaching presupposed that the corps receiving instructions were to form part of a regular army in the field, an army properly supported and reinforced by complete arms of the service. The resistance to the Militia Ballot Act must of necessity take the form of insurrectionary warfare, if the resisters are determined to fight in Ireland for Ireland instead of on the Continent for England. Such insurrectionary warfare would be conducted upon lines and under conditions for which textbooks made no provision.

“In short, it means barricades in the streets, guerrilla warfare in the country.”

In his article, ‘The hope of Ireland’, published in the Irish Worker of 31 October 1914, Connolly not only outlined the role of the Irish working class in the national revolution, but importantly made clear that Irish workers should bear no enmity for English workers; rather, he saw the liberation of Ireland as a condition for the victory of the British proletariat.

“The present crisis in Ireland is shattering many reputations and falsifying many predictions, but to the careful observer it is becoming daily apparent that it will leave intact at least one reputation, that of those who pinned their faith to the working class as the anchor and foundation of any real nationalism that this country can show. Here and there the working class may waver, here and there local influences may exert sufficient pressure to weaken or corrupt the manhood of the workers, but speaking broadly it remains true that in that class lay the only hope of those who held fast to the faith that this Ireland of ours is a nation distinct and apart from all others, and capable of working out its own destiny and living its own life.

“The working class has ever refused to be drawn into any mere anti-English feeling; it refuses to be drawn into it now. It has always refused to consider that hatred of England was equivalent to love of Ireland, or that true patriotism required an Irishman or woman to bear enmity to the toiling masses of the English population. It still holds that position.

“The working class of Ireland, when grown conscious of its true dignity, does not consider that it owes to the British Empire any debt except that of hatred. But it also realises that the best services it can render to the British people is due to them, and that service will be and will take the form of as speedy as possible a destruction of the foul governmental system that has made the British people an instrument of the enslavement of millions of the human race, of the extirpation of whole tribes and nations, of the devastation of vast territories. Enslaved socially at home, the British people have been taught that what little political liberty they do enjoy can only be bought at the price of the national destruction of every people rising into social or economic rivalry with the British master class. If it requires war to free the minds of the British working class from that debasing superstition, then war we shall have, for the world cannot progress industrially whilst so important a nation in Europe is perverted mentally by a belief so hostile to fraternal progress; if it requires insurrection in Ireland and through all the British dominions to teach the English working class they cannot hope to prosper permanently by arresting the industrial development of others, then insurrection must come, and barricades will spring up as readily in our streets as public meetings do today.

“Those who hold that the British people must learn this lesson are not necessarily enemies of the British people, of the British democracy. Rather do they hold . . . they are the truest friends of the British people who are the greatest enemies of the British government.”

Failure of anti-war movement in western imperialist countries

In 1915, Connolly again, and in greater detail, turned his attention to some of the reasons why socialists had failed to stop the war and what would need to be done to stop the war. Addressing readers in the United States in particular, in his article ‘Revolutionary unionism and war’, published in the March 1915 edition of the International Socialist Review, Connolly said that:

“I believe that the socialist proletariat of Europe in all the belligerent countries ought to have refused to march against their brothers across the frontiers, and that such refusal would have prevented the war and all its horrors, even though it might have led to civil war. Such a civil war would not, could not, possibly have resulted in such a loss of socialist life as this international war has entailed, and each socialist who fell in such a civil war would have fallen knowing that he was battling for the cause he had worked for in days of peace, and that there was no possibility of the bullet or shell that laid him low having been sent on its murderous way by one to whom he had pledged the ‘lifelong love of comrades’ in the international army of labour.”

Developing a theme, at least in part, that today, in very similar terms, we put forward under the slogan, ‘only the working class can stop the war’, Connolly observed:

“First, that labour could only enforce its wishes by organising its strength at the point of production, ie, the farms, factories, workshops, railways, docks, ships – where the work of the world is carried on, the effectiveness of the political vote depending primarily upon the economic power of the workers organised behind it . . .

“In all the belligerent countries of western and central Europe the socialist vote was very large; in none of these belligerent countries was there an organised revolutionary industrial organisation directing the socialist vote nor a socialist political party directing a revolutionary industrial organisation.

“The socialist voters having cast their ballots were helpless, as voters, until the next election; as workers, they were indeed in control of the forces of production and distribution, and by exercising that control over the transport service could have made the war impossible. But the idea of thus coordinating their two spheres of activity had not gained sufficient lodgement to be effective in the emergency.

“No socialist party in Europe could say that rather than go to war it would call out the entire transport service of the country and thus prevent mobilisation. No socialist party could say so, because no socialist party could have the slightest reasonable prospect of having such a call obeyed . . .

“To sum up then, the failure of European socialism to avert the war is primarily due to the divorce between the industrial and political movements of labour. The socialist voter, as such, is helpless between elections. He requires to organise power to enforce the mandate of the elections and the only power he can so organise is economic power – the power to stop the wheels of commerce, to control the heart that sends the life blood pulsating through the social organism.”

And it was in this spirit of working-class internationalism that, in ‘Strikes and Revolution’, published in the Workers’ Republic of 24 July 1915, Connolly acclaimed a victory by striking South Wales miners:

“We wish this week to congratulate our Welsh comrades upon the successful outcome of their resistance to the attempt of the government to dragoon them into submission. We congratulate them all the more heartily because we realise that had the government succeeded in terrorising them we might all have bidden a long farewell to our industrial liberties. Successful in Wales, the capitalist class that runs these islands would have been ruthless in Ireland. We are aware, of course, that the people of this country do not possess the same public rights as are freely exercised in Great Britain. But we also know that the measure of liberty enjoyed in Great Britain has a direct bearing upon the measure of liberty permitted in Ireland.

“That which the people of England enjoy as a right we in Ireland are sometimes permitted to exercise as a great favour, but if the people of England can only enjoy it as a favour, then we will never be allowed it at all. Every loss of freedom in England entails a still greater loss in Ireland; every victory for popular liberty in England means a slight loosening of our shackles in Ireland. This is humiliating, as everything in Ireland is humiliating today. But we do not destroy the humiliation by refusing to recognise it. The humiliation is part and parcel of the price we pay for the degradation of being members of a subject nation – fit only to fight the battles of their conquerors.

“The Welsh miners have attested the value of solidarity. They demonstrated that the government feared to prosecute any resolute body which defied them, and to the cautious whispers of those who declared that the government desired to make an example of them, they fearlessly answered that they were ready any time that the government wanted to try that sort of thing.

“This was the right spirit. It proves again that the only rebellious spirit left in the modern world is in the possession of those who have been accustomed to drop tools at a moment’s notice in defence of a victimised or unjustly punished comrade. The man who is prepared to lose his job in defence of a comrade is prepared to lose his life in the same or a greater cause, and, out of such willingness to sacrifice, the perfect fighting army of revolution may at any moment be fashioned.”

Preparation for the Easter Rising

Connolly greeted the momentous year of 1916, the last year of his life, with a 1 January editorial in the Workers’ Republic entitled ‘A Happy New Year’. He conceded that it must have seemed like a forlorn hope:

“Over all the world, the shadow of war lies heavy on the hearts of every lover of humankind. Over a great part of the world, war itself is daily taking its toll, and the gashed and mangled limbs of many thousands are daily scattered abroad, an affront to the sight of God and man. In the British Empire, of which we are unluckily a part, the ruling class has taken the opportunity provided by the war to make a deadly onslaught upon all the rights and liberties acquired by labour in a century of struggling; and found the leaders of labour as a rule only too ready to yield to the attack and surrender the position they ought to have given their lives to hold. Were the war to end tomorrow, the working class of these islands would be immediately launched into a bitter fight to resist the attempt of the capitalist class to make permanent all the concessions the too pliant trade union leaders have been swindled into conceding upon the plea of war emergencies.”

But he concluded with words that provide an important clue to his thinking, at the time when he was prevailing upon the leaders of the Irish Volunteers and the Irish Republican Brotherhood the urgent need for a rising:

“A Happy New Year! Ah, well! Our readers are, we hope, rebels in heart, and hence may rebel even at our own picture of the future. If that is so, let us remind them that opportunities are for those who seize them, and that the coming year may be as bright as we choose to make it. We have sketched out the future as it awaits the slave who fears death more than slavery. For those who choose to advance to meet Fate, determined to mould it to their purpose, that future may be as bright as our picture is dark.”

In ‘The days of March’, published in the 11 March 1916 issue of the Workers’ Republic, noting that this month marked the anniversaries of Robert Emmet, who had led an abortive rising against British rule and was hanged in Dublin in 1803, and of the Fenian Rising of 1867, which inter alia led to the hanging of the three Manchester Martyrs, Connolly wrote:

“In these days of March, let us remember that generations, like individuals, will find their ultimate justification or condemnation not in what they accomplished, but rather in what they aspired and dared to attempt to accomplish. The generation or the individual that is stricken down in the attempt to achieve a high and holy thing is itself therefore high and holy. By aspiring to reach a height the generation or the individual places its soul unassailably upon that height, even should its body be trampled in the mud at its base.”

On 8 April, as the rising drew near, Connolly published his article ‘The Irish flag’ in the Workers’ Republic, in which he again outlined his nationalist and internationalist perspectives and made clear his intentions to all who could grasp that this was a man who meant what he said.

He began:

“The Council of the Irish Citizen Army has resolved, after grave and earnest deliberation, to hoist the green flag of Ireland over Liberty Hall, as over a fortress held for Ireland by the arms of Irishmen.”

The global significance of this he defined as follows:

“The power which holds in subjection more of the world’s population than any other power on the globe, and holds them in subjection as slaves without any guarantee of freedom or power of self-government, this power that sets Catholic against Protestant, the Hindu against the Mohammedan, the yellow man against the brown, and keeps them quarrelling with each other whilst she robs and murders them all – this power appeals to Ireland to send her sons to fight under England’s banner for the cause of the oppressed. The power whose rule in Ireland has made of Ireland a desert, and made the history of our race read like the records of a shambles, as she plans for the annihilation of another race, appeals to our manhood to fight for her because of our sympathy for the suffering, and of our hatred of oppression.”

On this basis, Connolly declared, in words that, as we have seen, may be considered his hallmark and which have lost none of their resonance and global significance with the passage of 98 years:

“We are out for Ireland for the Irish. But who are the Irish? Not the rack-renting, slum-owning landlord; not the sweating, profit-grinding capitalist; not the sleek and oily lawyer; not the prostitute pressman – the hired liars of the enemy. Not these are the Irish upon whom the future depends. Not these, but the Irish working class, the only secure foundation upon which a free nation can be reared.

“The cause of labour is the cause of Ireland; the cause of Ireland is the cause of labour. They cannot be dissevered. Ireland seeks freedom. Labour seeks that an Ireland free should be the sole mistress of her own destiny, supreme owner of all material things within and upon her soil. Labour seeks to make the free Irish nation the guardian of the interests of the people of Ireland, and to secure that end would vest in that free Irish nation all property rights as against the claims of the individual, with the end in view that the individual may be enriched by the nation, and not by the spoiling of his fellows.

“Having in view such a high and holy function for the nation to perform, is it not well and fitting that we of the working class should fight for the freedom of the nation from foreign rule, as the first requisite for the free development of the national powers needed for our class? It is so fitting. Therefore, on Sunday 16 April 1916, the green flag of Ireland will be solemnly hoisted over Liberty Hall as the symbol of our faith in freedom, and as a token to all the world that the working class of Dublin stands for the cause of Ireland, and the cause of Ireland is the cause of a separate and distinct nationality.”

It is said that, before the rising, Connolly was asked what were its chances of success, only to reply: ‘None whatsoever.’ And, although there was fighting outside Dublin, for various reasons, planned uprisings in various other parts of the country failed to materialise at the right time, making immediate defeat all the more inevitable for the revolutionaries.

Why then did he insist on going through with it? There can surely be only one answer – as a thoroughgoing revolutionary, he was prepared to do whatever needed to be done at that historical moment, no matter what the cost to himself. On 6 April 1979, the South African apartheid regime hanged a young ANC and Umkhonto we Sizwe revolutionary named Solomon Mahlangu. On his way to the gallows he said: ‘My blood will nourish the tree that will bear the fruits of freedom.’

That is the statement of a revolutionary in the Connolly mould.

The Last Statement of the great James Connolly reads as follows:

“To the Field General Court Martial, held at Dublin Castle, on May 9th, 1916:

“I do not wish to make any defence except against charges of wanton cruelty to prisoners. These trifling allegations that have been made, if they record facts that really happened, deal only with the almost unavoidable incidents of a hurried uprising against long established authority, and nowhere show evidence of set purpose to wantonly injure unarmed persons.

“We went out to break the connection between this country and the British Empire, and to establish an Irish Republic. We believed that the call we then issued to the people of Ireland, was a nobler call, in a holier cause, than any call issued to them during this war, having any connection with the war. We succeeded in proving that Irishmen are ready to die endeavouring to win for Ireland those national rights which the British government has been asking them to die to win for Belgium. As long as that remains the case, the cause of Irish freedom is safe.

“Believing that the British government has no right in Ireland, never had any right in Ireland, and never can have any right in Ireland, the presence, in any one generation of Irishmen, of even a respectable minority, ready to die to affirm that truth, makes that government for ever a usurpation and a crime against human progress.

“I personally thank God that I have lived to see the day when thousands of Irish men and boys, and hundreds of Irish women and girls, were ready to affirm that truth, and to attest it with their lives if need be.

“JAMES CONNOLLY

“Commandant-General, Dublin Division

“Army of the Irish Republic”

Assessment of the Easter Uprising

It is conventional wisdom that there was considerable hostility to the leaders and fighters of the rising in the days following its suppression and there is doubtless an element of truth in that. But it was not the whole story. Many of those who looked on as the revolutionaries were taken away were said to be cowed rather than hostile, and a Canadian journalist, Frederick Arthur McKenzie wrote that in poorer areas ‘there was a vast amount of sympathy with the rebels, particularly after the rebels were defeated’.

The vengeful response of the British authorities, and especially the execution of a dying James Connolly, proved to be exactly the kind of action that Comrade Mao Zedong described as ‘lifting a rock only to drop it on one’s own feet’. In the general election of 14 December 1918, Sinn Fein won 73 out of the 105 Irish seats on a platform of abstentionism and Irish independence. On 21 January 1919, the newly elected Sinn Fein MPs convened the First Dail and declared the independence of the Irish Republic. The Irish War of Independence began later that same day.

An event such as the Easter Rising inevitably became a source of controversy in the wider socialist movement.

Under the title, ‘On the events in Dublin’, Leon Trotsky contributed an article to the 4 July 1916 edition of Nashe Slovo. The article does not mention Connolly, but rather pegs itself on the then impending execution of Sir Roger Casement, which was to take place in Pentonville Prison on 3 August 1916.

Casement hailed from an established Anglo-Irish Protestant family, but the Boer war in South Africa and his consular investigations, as a British civil servant, of Belgian atrocities in the Congo, as well as of similar atrocities inflicted on labourers on Peruvian plantations, led him to anti-imperialism and hence to Irish republicanism. He sought to obtain German support for an Irish rising and, on 21 April 1916, just days before the rising began, he was arrested at Banna Strand, Tralee Bay, County Kerry, as he attempted to bring ashore a consignment of German weapons that was far smaller than he had hoped to secure.

Trotsky at this stage was still playing his game of attempting to manoeuvre between the Bolsheviks and Mensheviks and he was far too cunning as to condemn the rising outright. Indeed, he made non-specific but sharp criticisms of the pro-imperialist positions taken up by Plekhanov and by the British social democrat HM Hyndman.

Yet Trotsky’s real and actual position was no less counter-revolutionary than that of those he condemned. For him, the Irish revolutionaries were nothing but dreamers. He wrote as follows:

” In so far as the affair concerned the purely military operations of the insurrectionaries, the government, as we know, turned out comparatively easily to be master of the situation. The general national movement, however it was expressed in the heads of the nationalist dreamers, did not materialise at all (‘On the events in Dublin’ by L Trotsky, Nashe Slovo, 4 July 1916).”

From this, Trotsky drew a conclusion that could not be more wrong, whether viewed from the ensuing century of Irish or of world history:

“The historical basis for the national revolution had disappeared even in backward Ireland.”

Indeed, Trotsky could not even conceive of an independent Ireland at all, but only of Ireland as a plaything of the different imperialist powers:

“In a pamphlet written on the eve of the war, Casement, speculating about Germany, proves that the independence of Ireland means the ‘freedom of the seas’ and the death blow to the naval domination of Britain. This is true in so far as an ‘independent’ Ireland could exist only as an outpost of an imperialist state hostile to Britain and as its military naval base against British supremacy over the sea routes.”

Writing in the same month, a famous socialist provided a starkly different assessment of the events in Ireland from that given by Trotsky. His name was VI Lenin.

In ‘The Irish Rebellion’, being Chapter 10 of his ‘The Discussion on Self Determination Summed Up’, Lenin began:

“Our theses were written before the outbreak of this rebellion, which must be the touchstone of our theoretical views.

“The views of the opponents of self-determination lead to the conclusion that the vitality of small nations oppressed by imperialism has already been sapped, that they cannot play any role against imperialism, that support of their purely national aspirations will lead to nothing, etc. The imperialist war of 1914-16 has provided facts which refute such conclusions.”

Lenin may not have been aware of Trotsky’s article when he wrote his own, but he was certainly aware of its theoretical standpoint. Similar views had been expressed by Karl Radek, and Lenin responded as follows:

“On 9 May 1916, there appeared in Berner Tagwacht the organ of the Zimmerwald group, including some of the leftists, an article on the Irish rebellion entitled ‘Their Song Is Over’ and signed with the initials KR. It described the Irish rebellion as being nothing more nor less than a ‘putsch’, for, as the author argued, ‘the Irish question was an agrarian one’, the peasants had been pacified by reforms, and the nationalist movement remained only a ‘purely urban, petty-bourgeois movement, which, notwithstanding the sensation it caused, had not much social backing’.

“It is not surprising that this monstrously doctrinaire and pedantic assessment coincided with that of a Russian national-liberal Cadet . . . who also labelled the rebellion ‘the Dublin putsch’.

“It is to be hoped that, in accordance with the adage, ‘it’s an ill wind that blows nobody any good’, many comrades, who were not aware of the morass they were sinking into by repudiating ‘self-determination’ and by treating the national movements of small nations with disdain, will have their eyes opened by the ‘accidental’ coincidence of opinion held by a Social Democrat and a representative of the imperialist bourgeoisie!!

“The term ‘putsch’, in its scientific sense, may be employed only when the attempt at insurrection has revealed nothing but a circle of conspirators or stupid maniacs, and has aroused no sympathy among the masses. The centuries-old Irish national movement, having passed through various stages and combinations of class interest, manifested itself, in particular, in a mass Irish National Congress in America . . . which called for Irish independence; it also manifested itself in street fighting conducted by a section of the urban petty bourgeoisie and a section of the workers after a long period of mass agitation, demonstrations, suppression of newspapers, etc. Whoever calls such a rebellion a ‘putsch’ is either a hardened reactionary, or a doctrinaire hopelessly incapable of envisaging a social revolution as a living phenomenon.

“To imagine that social revolution is conceivable without revolts by small nations in the colonies and in Europe, without revolutionary outbursts by a section of the petty bourgeoisie with all its prejudices, without a movement of the politically non-conscious proletarian and semi-proletarian masses against oppression by the landowners, the church, and the monarchy, against national oppression, etc to imagine all this is to repudiate social revolution. So one army lines up in one place and says, ‘We are for socialism’, and another, somewhere else and says, ‘We are for imperialism’, and that will be a social revolution! Only those who hold such a ridiculously pedantic view could vilify the Irish rebellion by calling it a ‘putsch’.

“Whoever expects a ‘pure’ social revolution will never live to see it. Such a person pays lipservice to revolution without understanding what revolution is.”

Lenin continued to hammer his point home:

“The socialist revolution in Europe cannot be anything other than an outburst of mass struggle on the part of all and sundry oppressed and discontented elements. Inevitably, sections of the petty bourgeoisie and of the backward workers will participate in it – without such participation, mass struggle is impossible, without it no revolution is possible – and just as inevitably will they bring into the movement their prejudices, their reactionary fantasies, their weaknesses and errors. But objectively they will attack capital, and the class-conscious vanguard of the revolution, the advanced proletariat, expressing this objective truth of a variegated and discordant, motley and outwardly fragmented, mass struggle, will be able to unite and direct it, capture power, seize the banks, expropriate the trusts which all hate (though for different reasons!), and introduce other dictatorial measures which in their totality will amount to the overthrow of the bourgeoisie and the victory of socialism, which, however, will by no means immediately ‘purge’ itself of petty-bourgeois slag.”

For the avoidance of doubt, he continued:

“The struggle of the oppressed nations in Europe, a struggle capable of going all the way to insurrection and street fighting, capable of breaking down the iron discipline of the army and martial law, will ‘sharpen the revolutionary crisis in Europe’ to an infinitely greater degree than a much more developed rebellion in a remote colony. A blow delivered against the power of the English imperialist bourgeoisie by a rebellion in Ireland is a hundred times more significant politically than a blow of equal force delivered in Asia or in Africa . . .

“The dialectics of history are such that small nations, powerless as an independent factor in the struggle against imperialism, play a part as one of the ferments, one of the bacilli, which help the real anti-imperialist force, the socialist proletariat, to make its appearance on the scene.